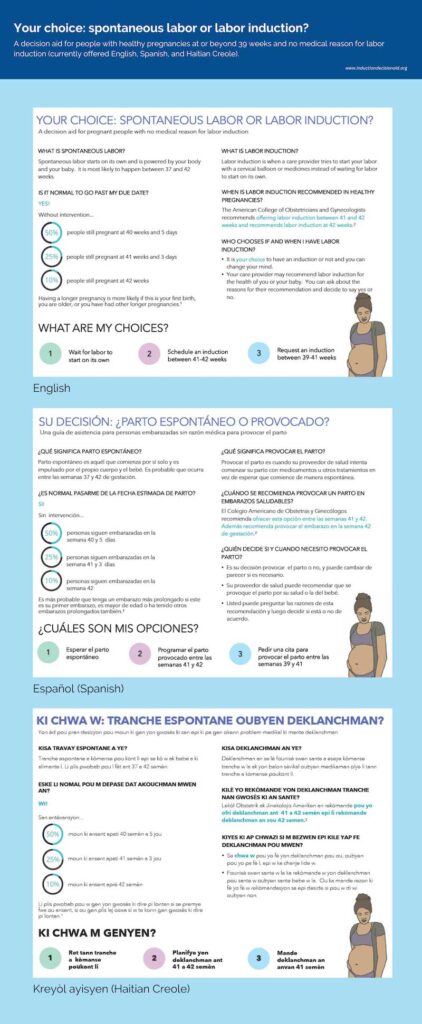

I wanted to address a question I’ve been getting a lot. It typically goes something like this: “I’m getting to the end of pregnancy. My doctor is suggesting we induce at 39 weeks; she says that the most recent evidence says this is better for the baby. Should I do it?”

This question comes up even in the absence of a viral pandemic, but the current situation has made it more salient. A scheduled induction gives an added measure of control over the timing of birth. So: is it a good idea? (Note: I am grateful to my coauthor/friend/NY OB Spencer McClelland for conversations and writing on this).

To understand both why we’d ask this question and why this discussion has gotten so much more common in the last year or so, we want to step back. Until relatively recently, the conventional wisdom had been that inductions are a “setup” for a C-section. Think about, for example, the Ricki Lake documentary The Business of Being Born, which (basically) castigates inductions as the beginning of the “cascade of interventions” which end in a C-section.

There is some logic here: the physiologic principle is that the body should respond much more readily to its own signals for when to go into labor, so it stands to reason that inducing labor with medications may be less effective. And it is true that if you compare women who are induced to those who are not, inductions are associated with higher C-section rates.

But this correlation is just that, a correlation. Women who are induced are different in other ways than those who are not — they are likely to be higher risk on other dimensions — and it may be those characteristics (and not the induction) which lead to the higher C-section rates. To answer this convincingly, we need randomized data.

This is precisely what we now have, in the form of a fairly recent study called the ARRIVE Trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2018. Here’s the basic structure. The study recruited around 6000 low risk women having their first child; they were invited into the study in late pregnancy. Half of the women were chosen randomly for the “Induction at 39 weeks” treatment group and half were chosen for the “Expectant Management” group. The latter group was, as the term implies, managed expectantly and either went into labor on their own or were induced later in pregnancy (usually by 41 weeks).

(The study didn’t “force” women into these choices — this is run with what is called an “encouragement design” so women were encouraged to adhere to the treatment they were assigned but were able to make their own choices. In practice, the compliance with assigned group was high.)

The study had two main outcomes. First: babies. The babies born did equally well in the two groups. More precisely, there was no statistically significant difference in “adverse perinatal outcomes.” Second: C-section rates. This was the striking result. Those induced at 39 weeks actually had lower C-section rates (18.6% versus 22.2%) than those who were expectantly managed.

It is this latter result which has gotten the most attention and, I think, significantly affected practice. Doctors and patients who may have been reluctant to induce before now see the possibility of not only not increasing C-sections, but actually decreasing them.

This is a really excellent study. It’s large, it’s randomized. It was focused in the sense of having a clear set of outcomes. In my view, it is appropriate that this change some choices. Relative to the case before this, I’d be much more comfortable personally inducing at 39 weeks.

I do, however, want to raise two caveats here which I think should give us pause in using these results to conclude that all pregnant women should be induced at 39 weeks.

The first issue is with what we’d call “external validity.” Basically, the question of whether the results from this particular trial should be assumed to hold for all women in all situations. There are some reasons to think they might not. The trial was run in hospitals with generally low C-section rates, and the study population was healthy, low-risk women. In addition, it is possible that when doctors knew they were being watched as part of the study, they did things differently (this is what is sometimes called a “Hawthorne Effect”).

All this is to say that this headline finding that 39-week induction reduces a woman’s risk of a C-section might actually not be true when medicine is practiced in the real world. Or it might be true for patients and hospitals that resemble the hospitals in the trial, but less so for patients and hospitals who are different.

A second issue I’d flag is the importance of preferences. Many women giving birth have some sense of the experience they would like. When I was pregnant I wanted – if possible — to go into labor at home, stay there for as long as possible and avoid an epidural. This isn’t what everyone wants! But it was also incompatible with induction. Of course, if an induction was the safest for me and the baby, I’d have done it. But my preference was not to.

Reading these data, I think they are supportive of 39 week inductions but certainly not so strongly that they’d overwhelm strong preferences in other directions. If you want to do it, this is reassuring. If you don’t, I certainly do not read the data as saying you have to induce.

I will issue one caveat: a Swedish trial from last year suggested that one can possibly push expectant management too far. In particular, they found that waiting until 42 weeks to induce, rather than inducing at 41 weeks, caused an increase in stillbirths. This is thankfully a rare outcome but the differences were large enough that the study stopped early. Obviously 41 weeks and 39 weeks are different, but I thought it useful to note this in the same space.