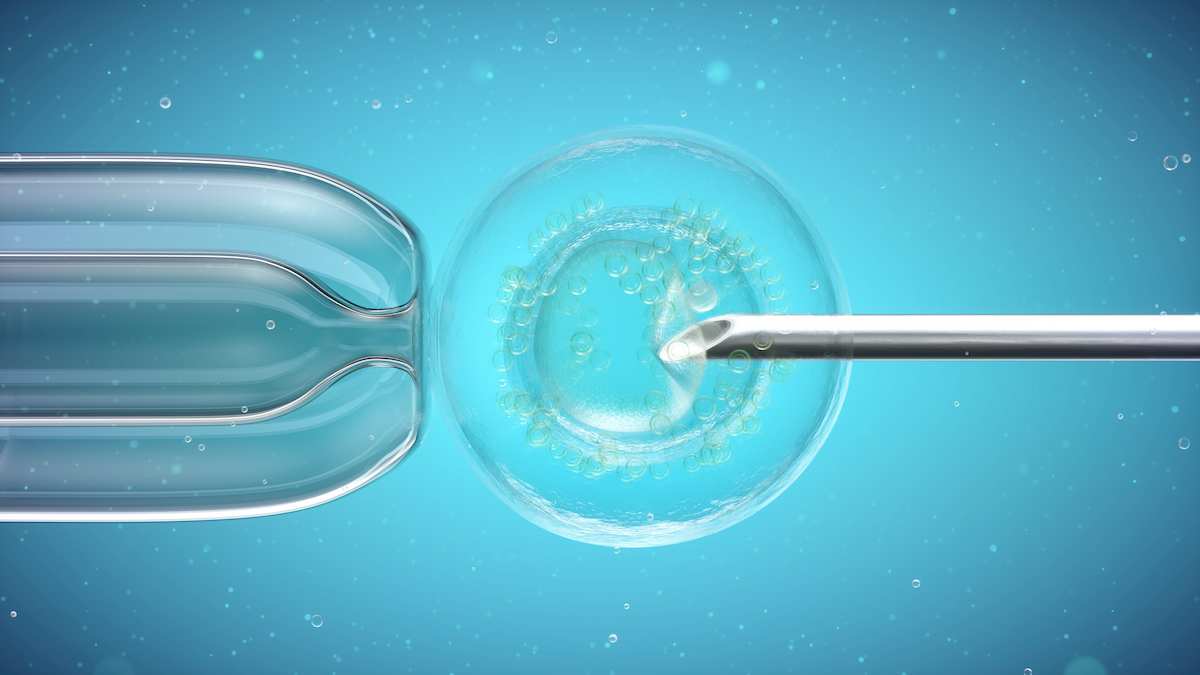

After a pretty traumatizing level II ultrasound, I’m curious if there has been any research conducted that compares the “potential complications” doctors have delivered to patients and how often those “potential” diagnoses are confirmed or disproven after further testing or once the baby is born.

Example: I was told my 21-week-old baby “likely” has tetralogy of Fallot, and because he’s also measuring small, there’s a “45% chance” of a genetic abnormality as well. After digesting that news and sharing it with family and close friends, I’ve discovered nearly every parent I’ve discussed this with told me their doctors also warned them about a genetic abnormality and/or a heart defect, only for those potential diagnoses to disappear upon further testing. I’m interested in understanding if the approach doctors take is a “CYA” sort of thing, even though it puts enormous stress on the expecting parents, or if they ever go back and analyze how often they’ve flagged a complication inaccurately. I feel like I’ve been forced onto an emotional roller coaster only to (potentially) end up at the exact same place I started!

—Casey

That’s a great question and I’m sorry you’re going through this stressful experience. I can only answer how I do it myself, as I am sure it varies from doctor to doctor. When I am sharing “news” with a patient, it’s a delicate balance between being as descriptive and honest as possible, and also trying to do it in a way that doesn’t overly scare someone. It’s hard to deliver any news about a finding in the baby that won’t scare people to some degree, of course, but I am trying to match the level of worry with the situation at hand. Some situations are less risky and should be less anxiety-provoking, and other situations are legitimately more worrisome and will (and should) cause more worry. But we as doctors frequently fail, even if we try really hard to get it right. This is because the conversation is ultimately a human (doctor) to human (patient) interaction, and humans are all very different in how they process fear, statistics, health, and so on. I can do the exact same thing with two patients, and one of them may be minimally worried and the other terribly scarred. So we try to “read the room” as best we can. Personally, I try to give accurate percentages and try to place that into the context of other risks. I try to be as honest as possible — not overstating the risk, but also not ignoring it.

We also do our best to get the diagnosis right! Or at least state what we are seeing that leads us to think there might be a problem and what we are going to do to figure that out. That happens all the time: we see something that might mean something, but might not. It’s a tough spot to be in as a patient, but unfortunately that is the reality in medicine — it often takes a while to get from suspicion to answer. We do our best to get people from point A to point B as quickly as possible and with as much information (as they want) as possible during that process.

If you (or anyone else reading this) is in a similar predicament, some useful direct questions to ask your doctor might be (I will call the condition “X”):

- Are you telling me my baby has X, or there is a chance my baby has X?

- If only a chance, what do you think that chance is? This can be a specific percentage, or at least break it down into less than 10%, 10% to 50%, more than 50% (or any other grouping you find helpful).

- What are we going to do to find out one way or the other? How long will it take? Might we not know until after birth?

- If my baby does have X, what does that mean for the baby? What is the likelihood this will be a serious issue for him/her? If you do not know the answer to this, which is okay, can I meet with other doctors/specialists to discuss what that means for after birth? Should I be doing that now or waiting until we know for sure?

In general, ask very direct questions. If you want to know something, you should ask! We don’t always know what patients want to know.

Community Guidelines

Log in