My family have always been runners.

My favorite picture of one of my younger brothers is when he’s perhaps 5 or 6, crossing the finish line of a race, stopping his watch. It’s not just that he was running races at this age, it’s that he was concerned about his time. This kind of slightly extreme attitude toward recreational running has had a hold over me, that brother, and my dad more or less since I can remember (my mom and the other brother were largely spared).

When I was a kid, I vividly remember Dad’s quest for the sub-3-hour marathon. He finally got it in the 1987 Philadelphia Marathon (2:58:45). It was the era before cellphones, so we didn’t find out until he got home, and I recall standing on the porch and just how happy he was.

We are all familiar with that chasing of the PR [personal record], of trying to hit some elusive round time goal. It’s easy to see the accomplishment there. But there is also the unfortunate reality that, as we age, it gets less realistic. At 42, I ran some PRs last year, but only because I moved to distances I hadn’t done before (the “auto-PR”). My dad is 80 now. He still runs most days, and is always trying to get faster, but the 3-hour marathon isn’t in reach.

What do we chase when we can’t chase the PR? One option is chasing other people — we can try to hit age-group wins and age-group times. But most of us aren’t winning age groups. And for many of us, the competition with ourselves has long been our main driving force. The question is: How can I compete with my younger self? How do I know if I’m outpacing her?

My dad, Ray Fair, asked the same question in the late 1980s, as he neared 50. In addition to sharing a love for running, he and I also share a love for data and a passionate belief that it can inform our lives in ways that other people might not expect. I’m an economist, and I have made a career of translating data into actionable insights for parents. My dad is also an economist, and while his focus is on more traditional economic topics (namely, the macroeconomy — he’s an economics professor at Yale), he could not avoid the temptation to use data to figure out where he stood relative to his past self.

In 1994, Dad published a paper in a reputable economics journal with the title “How Fast Do Old Men Slow Down?” The basic idea in the research is to ask, effectively, what the impacts of aging are at the upper limits of performance. A secondary use of this data is to translate it to our own running.

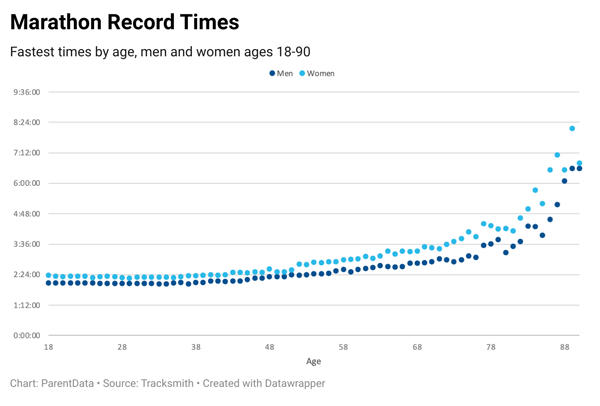

What the paper actually does is look at world records, by age, in various running events and fit-curves to them. To make this more concrete, I’ve pulled out the current single-year age records for men and women in the marathon in the graph below.

The graph suggests a particular shape to our age-based decline. First, performance is pretty flat up to age 40. There is then a pretty steady linear slowdown up until sometime in your 70s. After that, the decline begins to accelerate.

The analysis in the paper uses data like this to estimate (1) how slow the decline is in that first phase, after 40, (2) at what age the decline starts to accelerate, and (3) how fast it declines after that. From these numbers, it’s possible to calculate your own expected decline.

What the paper actually calculates is an expected percentage decline by age. What Dad ends up concluding is that your performance will decline by about 1% per year until age 77, and then much faster after that. This is an average that is pretty consistent across race distances. (Noting: For data limitation reasons, all the analysis is done on men. However, the graph above suggests that women look pretty similar.)

The result of all this is an expected percentage decline by year. We can then apply this to our own racing. If the world records represent the absolute minimum time by age, then the evolution across the records reflects the most optimistic view of how we can sustain our times. By applying this to ourselves, we can ask how much (or not!) we fall off this trend.

To give a more concrete example: Last year, I ran a half-marathon in 1:34:52. I was 42. This year, I’m 43. Based on last year’s time, I should be able to run 1:35:47 this year — that’s a bit of a slowdown. Anything faster than that, even if slower than 1:34:52, would be an “age-graded PR.”

In the space of a year or two, especially before that pivot around 77, this doesn’t make a huge difference. But the years do add up to mattering. Dad has all of his marathon times up on his website (of course), and he noted for me that his best corrected age time is at age 53, when he ran a 3:10 marathon. Based on age grading, his sub-3-hour performance was only his third-best effort.

Age-grading yourself in this way can make you feel better about your current performances. It also has the side effect of making you feel worse about your earlier ones. For example: Let’s say I am able to accomplish my goal of running 1:32:00 in my next half-marathon, at age 43. On one hand, I’ll feel great. On the other hand, this tells me that I could have run as fast as 1:31:06 last year, at 42. Not as great.

[Author’s note: After this piece was written, I did run a PR in the half, 1:30:52. What this tells me, heartbreakingly, is I could have run 1:29:57 at age 42. I missed my chance to go sub-1:30!]

The most complicated part of this analysis comes when we start to look at much older groups.

First problem: there just are not a lot of very, very old people running marathons. This is a problem for fitting the data. We can, perhaps, be reasonably confident about the decline between ages 40 and 50, when many people run competitively. But there are fewer people in their 80s running marathons at all, let alone for time. This is especially true for women — as Dad says in his paper, “More time is needed to build up a sample of old women running road races.”

The oldest age records also pose another conundrum. There are some extremely impressive times. Most notably, Ed Whitlock of Canada holds the records at ages 68, 69, 73, 74, 75, 76, 80, 81, 82, and 85. At 73, he ran 2:54:48. Using age grading, this would suggest Ed could have run a 2:05 marathon when he was 40. This would put him in the records in that age range too, but he is not anywhere to be seen. In fact, his fastest marathon ever was 2:31, at age 48. A very respectable time, but not close to a record.

What happened? Ed ran as a teenager but then he stopped, and he took it up again in his 40s. This leads to an interesting question: If he had been running all those years in between, would he have had the stamina (or the knees) to run under 4 hours at age 85? I’m not sure.

The advantage of the “world record” approach to the data is that we are really seeing the limits at each age. But the disadvantage is that we are not seeing the path of a single person, and it seems very plausible that the individuals who are performing well when they are old are different from those who perform well when they are younger. Not always true — [Olympian] Joan Benoit Samuelson is in there with the record for 53-year-olds — but often.

My dad said this slightly differently when we talked about it. This approach, he points out, assumes that, while people vary in their pace and capacity, their potential decline is similar to some biological minimum defined by elite runners. In his view, this is perhaps not unreasonable for younger people, but as we age, there is just more variation and a lot less data. That leaves open space for one unusual person to really drive the results. Ed Whitlock may be a good metric of our maximum biological capacity, but he also may not reflect a reasonable path. This is underscored, I think, by the fact that the records at older ages are very concentrated in a few individuals.

A final interesting question: These data are based on the past. In an era of super-shoes, of better understanding of the value of cross-training, of better fueling options — could we age more slowly in our running? In 50 years, when we do these same estimations, would we find that the decline starts later, or goes less quickly? Impossible to say; perhaps we will have to wait until [world-record holder Eliud] Kipchoge is 75 to find out if he can beat his predicted age-adjusted marathon time (2:50).

What about my 80-year-old dad? The race he has most consistently run is the Labor Day 20K in New Haven. It’s been going for 45 years; he missed only two instances. He’s got his list of times, along with four friends who have also completed the race nearly every year. As he says:

Even though my best time ever was 1:18:40, at age 43, my best age-corrected time according to the age factors used on this site was 1:20:30 at age 48. The predicted minimum times [in his list] use the 1:20:30 performance at age 48 as the base. As you can see, my races since age 62 have been way off the regression line. The fault, I fear, is not in the line but in myself. The results for four other people reported on this site suggest that the line is fine.

This is spoken like a true lover of evidence. He’s willing to defend the data, even if it throws his running under the bus.

As many of you know, I like to run. And my go-to running clothes, which you will see if you watch my sweaty morning Instagram stories, are from Tracksmith. A few months ago, Tracksmith asked if I’d write something about running and data for Meter Magazine. I wrote about my dad, about research, and about using data to compete with your past self. Tracksmith generously agreed to let me reprint the piece here!

Community Guidelines

Log in