When I was young, my 1970s feminist mother instituted a prohibition against Barbie, which she felt promoted a negative image of women. She pointed out, correctly, that if Barbie were a real person she would be unable to stand, pulled down by the weight of her boobs. The body image wasn’t realistic, on top of the fact that (more in the 1980s than now) Barbie was defined primarily by her bikinis and relationship with Ken. I took the no-Barbie rule very seriously. When a friend who was moving away gave me a Skipper doll as a parting gift, I hid it in the closet. It’s probably still there, perhaps next to the wine cooler I stashed in the 11th grade.

As a kid, I was sure I would do things differently with my own children. They’d have all the Barbies they wanted, on top of never having to eat the peanut butter that you stir up to mix in the oil, which always gets crumbly at the bottom. As an adult, of course, I’m aiming to emulate my mom pretty much all the time. I unapologetically serve the crumbly peanut butter. We never quite live up to our parents, though, so I have not held the same line on Barbies. My children haven’t ever been really into them, it’s true, so I haven’t been fully tested.

This all came to mind last week, when someone wrote me an email the crux of which is this paragraph:

I now have three girls. My oldest is a big fan of Disney princesses, and I have friends who make a big deal about how girls who like princesses grow up to be less successful than girls who like superheroes. I was wondering if the research supports that? And if so, what exactly “less successful” means?

I got curious reading this. What, precisely, do we know about Disney princesses and their impacts, nefarious or otherwise?

There is an excellent book from about a decade ago, called Cinderella Ate My Daughter, in which Peggy Orenstein explores the entire girly-girl culture, from princess play to child beauty pageants. The book talks through research around stereotypes and girls’ self-esteem and ambitions. Disney princesses are a part of the girly-girl culture. But the book, and the concerns, are about much more. It’s not clear that the princesses are all, or even a large part of, the story. This question needed more digging.

Maybe it’s surprising (or maybe not!), but there is a sizable academic literature on the Disney princesses. The most well-documented fact from it (see e.g. here) is that there has been significant evolution in the princesses over time, in particular in how traditionally feminine they are.

Conceptually, think about the difference between Snow White and Elsa (from Frozen) or Merida (from Brave). The plot of Snow White centers around the need for rescue by the prince. The plots of Frozen and Brave, on the other hand, do not revolve around getting a man, nor do either of these princesses end up with a wedding. They’re portrayed as strong and capable (albeit with some emotional baggage).

This comparison reflects a general trend in this set of films, which can be documented using various kinds of text analysis or structured coding of movie elements. The later princesses are less likely to collapse in hysterics (looking at you, Cinderella) and less likely to need saving by a handsome prince. Romantic love, which is central to the early princess movies, becomes less central in later ones. Princesses simper less and shoot more. They have also become somewhat more racially diverse; there is more to be done there.

The fact remains, though, that they are princesses. They wear dresses. They dance. They twirl! And many of these actions are traditionally female-associated. Does this mean that girls who play with princesses are destined to feel the need to adhere to more gender stereotypes?

Here, the research is much less clear.

What academics can do is look at how children interact with princess-themed activities. An example is this paper, which studied a sample of 3-to-5-year-olds. The researchers set up a structure where they gave children a box of costumes, some of which were Disney princess costumes and some not, and looked at how the kids played with them. They interviewed the children and their parents afterward.

They found that girls preferred the princess costumes (playing with them 59% of the time) and that much of the play focused around beauty. For example, one girl put on a Cinderella dress and said she looked pretty. The children engaged in princess-like movements while wearing the dresses. Twirling — which occurred in 11 of 27 participants — was the most common. Ballroom dancing also occurred. Boys were at least partially excluded from (or uninterested in) dressing as princesses or playing princess. They preferred the superhero costumes.

What do we make of this? My sense is that the observations will be familiar to many parents. The paper reporting these makes a link back to evidence that gender stereotypes can be harmful to girls, but this is indirect. It’s not clear from the research that this princess play is actually changing anything. It might be! It just isn’t obvious from what we see here.

Similarly, we have research that surveys children (like this study) and shows that girls who engage with more princess media also display more gender-typical behaviors and attitudes. But which direction the causality goes on that is unclear — is it the attitudes that cause the engagement, or vice versa?

What we do not have are studies that would (say) randomize long-term exposure to princesses while holding everything else constant. Sure, some parents keep their kids away from princess media (or, for my mom, Barbies), but those behaviors are likely linked to other change in media exposure. Apropos of the original question, there are no research studies that link metrics of adult “success” with princess exposure as a child.

Based on what we see, I think any such links are a big stretch. Further, as the princesses get less girly, these concerns become less salient.

There is, however, a final issue that deserves more discussion. Princesses may be less traditionally feminine in their behavior now, but — not to put too fine a point on it — their appearance hasn’t evolved much. They are all conventionally attractive. Shiny hair. Clear skin. Big breasts. They are all thin.

This is, of course, obvious from looking at pictures. But we can also study it with data. Like in this paper, which measured the waist-to-hip ratio of Disney princesses and found it was an average of 0:5. This was significantly smaller than in the villains (average of 0:66). It is totally unrealistic as an actual body feature. By comparison, at her thinnest, Kim Kardashian reported having a waist of 24 inches with hips of 39 inches. That’s a ratio of 0:61!

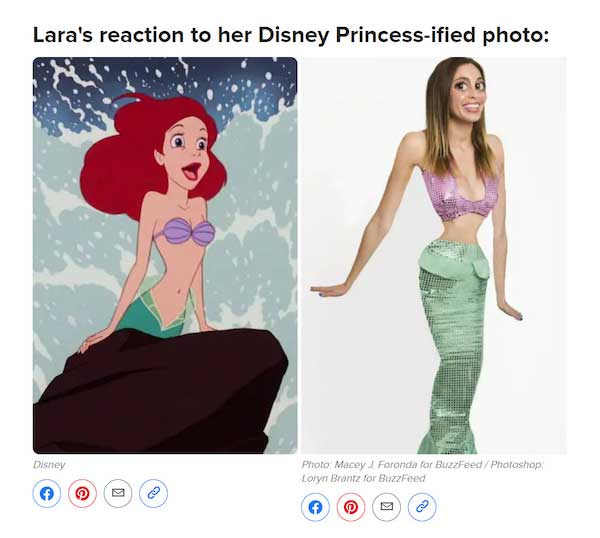

BuzzFeed (bless their hearts) published this amazing article in which staffers were Photoshopped into princess proportions. The Little Mermaid one below might be my favorite, as it further illustrates that the princess eyes are really out of proportion.

This proves that literally no one could look like Ariel (without significant and dangerous plastic surgery). But it doesn’t prove it matters for self-image. That is: we can’t know whether the princesses are fueling body-image issues any more than we can prove it for other media.

On the encouraging side, we have one randomized controlled trial of 120 girls between ages 3 and 6 in which body image wasn’t affected by princess media exposure. Granted, this is a short-term exposure and it’s just one trial. The ways in which modern society imposes a particular body ideal on girls are undoubtedly more complicated than one set of movies. Still, I don’t think it would kill Disney to introduce some princesses who were slightly more normal-size, or at least had biologically feasible human proportions.

To answer the original question: I do not see anything in the data that would suggest your child will be less successful if they like Disney princesses, although we’d likely do well to remind them as they age into puberty that princess proportions are not for people.

I would be remiss not to mention by far the best thing I read in doing this research, which is this essay by an eighth grader on the possible impact of Disney princesses on girls. It makes many excellent points about the insanity of the princesses’ appearance (e.g. “In the movie Frozen, it is very clear that Anna’s eye is bigger than her wrist, which is not true for a normal person”). The essay ultimately concludes that Disney princesses could cause girls to have an unrealistic body image. However, I personally came away thinking that if this middle-schooler is reflective of our youth, Disney has an uphill battle to ruin them.