Cytomelagovirus, or CMV, is a common herpesvirus. In adults and healthy children, the virus is typically mild or asymptomatic. Like most herpesviruses, the pattern of infection is an initial “primary” infection, and then subsequent latent infection, which can cause flare-ups. (Think about genital herpes or cold sores).

CMV infection is extremely common. In parts of the developing world, virtually 100% of adults have been infected; in developed countries it may be more like 50%. Still, this is extremely common.

Because CMV doesn’t cause manifest disease in most adults and children, you may not have heard of it. However: CMV is among the most common causes of birth defects in the US, with a rate of around 1 in 1000 births. These birth defects range from mild to severe or fatal, with hearing loss (in one or both ears) being the most common. However even with this risk, pregnant women often do not hear about this until it may be too late. I’m disappointed to say that CMV is not featured in Expecting Better (although it will be the next time I revise).

This information needs to be out there. So let’s review: what is it, what are the concerns, how much risk is there, and what can you do about it?

CMV manifestations in pregnancy

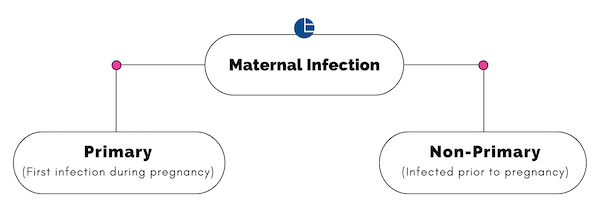

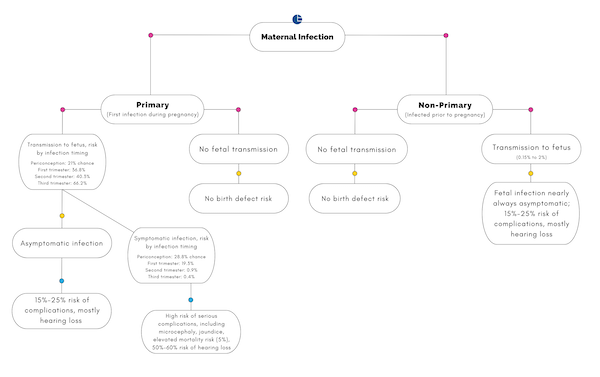

The landscape of CMV in pregnancy is, frankly, confusing. The seriousness of the disease for the infant depends on the timing of maternal infection and transmission to the fetus. To help understand, I built a little visual, which I’m going to walk through in steps.

To begin: Infections with herpesvirus are classified in two ways. “Primary” infection is the first time someone is infected; “Non-Primary” are later flare-ups. During pregnancy, CMV infection in the mother can be either primary — this is their first exposure — or non-primary. In the US, an estimated 50 to 80% of prime-age adults have evidence of previous CMV infection. People in this group who got pregnant would have “Non-Primary Infection”. For pregnant people without previous exposure, the yearly risk of developing a primary infection is estimated at around 2.3%. For pregnant people, young children in a household are a significant exposure risk.

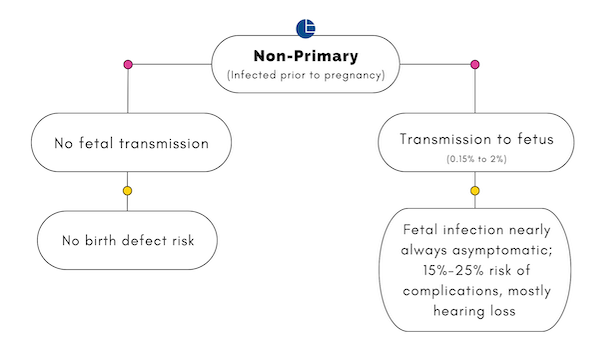

What this means is that most CMV infections in pregnancy are “non-primary”. The situation for pregnant people with a non-primary CMV infection is illustrated below. In most cases — 98 to 99% — non-primary infections are not transmitted to the fetus. In this case there is no CMV-related birth defect risk. However, in an estimated 0.15% to 2% of cases, there is transmission. Nearly all fetuses are asymptomatic in these cases, and generally do not show complications at birth. Unfortunately, an estimated 15 to 25% of these asymptomatic infections lead to later complications, most commonly hearing loss.

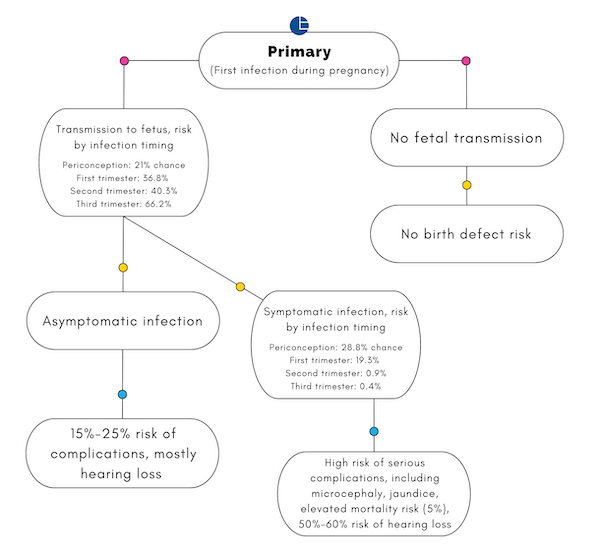

Primary CMV infection (infection among people who haven’t had it before) during pregnancy is much less common, but is more serious, as illustrated in the (more complicated) portion of the chart below. As with non-primary infection, if there is no transmission to the fetus, there is no CMV-related birth defect risk. However, transmission to the fetus during primary infection is much more common, and depends on the timing of infection during pregnancy.

Infection in the periconception period (4 weeks before to 6 weeks after the last menstrual period) is estimated to result in fetal transmission 21% of the time, for example. Transmission risk to the fetus is highest for infection in the third trimester.

Transmission to the fetus may then lead to asymptomatic infection — which would carry the same risks that it does when resulting from non-primary infection — or symptomatic infection, which is much more serious. Symptomatic infection most commonly results from infection early in pregnancy or right before.

Putting the transmission and symptomatic numbers together, primary CMV infection is most dangerous in the first trimester, where approximately 7% of CMV infections would lead to symptomatic illness in the fetus. Infection in the third trimester leads to symptomatic infection only about 0.2% of the time. The complications from symptomatic CMV infection in a fetus are variable and can be very serious. The mortality rate is estimated at 5%, and the risk of hearing loss is more than 50%.

I put this all together in a single chart, to navigate not so much what to do (more on that below) but how to think about this.

Can we lower CMV risk?

Given the serious and scary risks here, a natural question is: can they be lowered, and how?

The first best would be a vaccine, since CMV is a virus. When I talked with the Moderna CEO a few months ago, we talked briefly about their work to develop a CMV vaccine, which is currently underway. (You can learn more and get involved here).

For now, there is no vaccine, but there are possible approaches to lowering risk. The first thing to recognize is that you can only control or lower risk if you have never been infected with CMV before. If you are among the large share of the population who has had CMV, you are in the group with “non-primary” infection. On the one hand, this non-primary infection has relatively low risk. On the other hand, there is no risk mitigation to do.

How would you know if you were in this group? Testing. There are simple laboratory blood tests for CMV infection. These are not routinely ordered for pregnant people, which means both that there may be reluctance to order this testing and that insurance may not cover it. But you can ask.

There are good reasons why doctors may be reluctant to screen, largely reflecting the fact that there is not much to do, and either a positive or negative test can be scary. So this isn’t an obvious choice in either direction; it may depend on your own preferences.

If you haven’t been infected in the past, or you don’t know, there is a question of avoidance. For parents, small children are the most common vector of CMV; primary infection occurs about 25% of the time with a child shedding CMV, versus only 2% if they are not. Children can shed CMV virus for a long period of time after infection, and without a test (possible, very unlikely to be something you can access) it is hard to know if it is happening.

Enhanced hygiene behaviors (hand washing, avoiding intimate contact with urine or saliva) are suggested as ways to lower risks, with some limited evidence in favor of them. Of course, keeping up a long period of avoidance of your toddler is difficult.

Bottom line: risk reduction options here are limited. In my mind, there is a lot of value of getting a test. If you have a toddler and haven’t been exposed to CMV before, I think there is a strong argument for enhanced hand washing protocols and not sharing food with your baby or kissing them on the mouth. Yes, this is hard. It may also be worth it.

What if you are exposed?

Primary CMV infection during pregnancy appears, typically, as a flu-like illness. If you have such an illness, and if flu tests are negative, a CMV test is important. Pregnant people who have primary CMV infection should be carefully monitored for the possibility of complications with their infant. There are some newer treatment options, although nothing which has widespread agreement.

If this occurs, your doctor will be your best asset. An amniocentesis is common to test for fetal transmission, and frequent ultrasounds can detect physical abnormalities. Your baby will be more closely monitored both before and after birth.

Information and support

If you’d like to know more about this, try the National CMV Foundation. And if your pregnancy, baby or child has been affected by CMV, there are support groups.

Community Guidelines