Febrile seizures are often terrifying for parents. They are usually unexpected, and the physical symptoms are scary — a child’s body stiffens and twitches, they lose consciousness, and may urinate, defecate, or vomit. For many parents, the immediate fear of the moment is then quickly replaced with a worry about what a seizure might mean for long-term health. Does this suggest a risk for epilepsy? Does it mean an underlying neurological problem?

Below, I’ll walk through how to tell the difference between simple and complex febrile seizures, how common they are, and what you should do if your child is having one.

What is a febrile seizure?

A febrile seizure is a seizure that occurs in a child 6 months to 5 years, accompanied by a fever above 100.4 degrees. These seizures are common: an estimated 2% to 4% of children will have at least one. Family history of febrile seizures increases risk, but in most cases, these do not seem very predictable.

The most important distinction here is between a simple febrile seizure and a complex febrile seizure.

Any further discussion of recurrence risk, prognosis, and other possible associations depends on this categorization. Fortunately, it is a determination that can typically be made at the time of the seizure or at least within the first 24 hours.

Simple febrile seizures

A simple febrile seizure lasts less than 10 or 15 minutes and does not recur within 24 hours. Most seizures of this type last less than five minutes. These represent about 80% of febrile seizures.

As scary as it is when it happens, a simple febrile seizure generally has no long-term impacts and does not indicate a substantially elevated risk of more serious medical concerns.

Generally, after a first febrile seizure, a child will be seen by a medical professional (often in the ER). Once the child has returned to baseline and seems to be doing well, they generally do not have to be kept longer in the hospital and can return to normal activities (once they get over the illness that caused the fever). The three big questions that arise: Will it happen again? Can I prevent it? Does it predict long-term health risks?

How common are recurrences?

Recurrence of simple febrile seizures is fairly common. In one study of 428 children, researchers found 32% of those children had a recurrence after a first seizure, with most having only one additional one, but a small share (5.8%) had three or more. These figures are similar elsewhere.

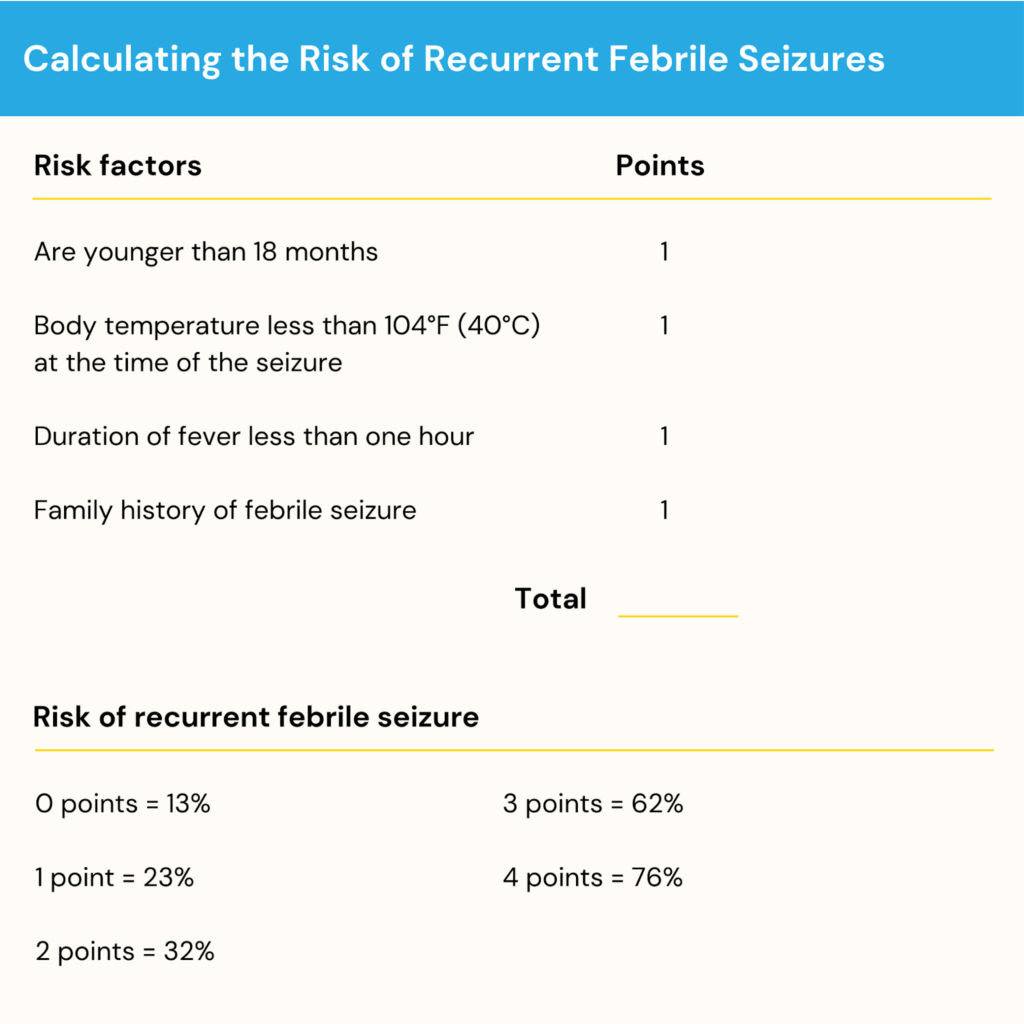

Recurrence is more common if children are younger at the age of the first seizure, if they have a family history of febrile seizures, if the fever was lower at the time of the seizure, and if there was a short onset between the fever and the seizure. The calculation below, based on the reference above, is a simple approach to predicting the risk of recurrence based on these four factors.

To be clear: recurrence of these seizures doesn’t mean long-term issues or serious medical concerns. It is simply a predictor of whether the same type of thing will happen again. One reason this is good to know is that you should be in a position to prepare other caregivers for the possibility of recurrence.

Can I prevent it?

Febrile seizures occur as a result of a fever. A natural question is whether limiting fever decreases the risk of seizure. The answer, based on randomized trials, seems to be no. Treatment of children with medications such as Tylenol or Motrin to lower fever does not reduce the risk of seizures. It is worth noting that there is some evidence that treating fever during an illness episode that results in a seizure might decrease the risk of recurrence during that illness episode.

There are many different reasons (beyond seizure risk) why you might want to treat a fever. Unfortunately, it’s not clear why treating fever isn’t an effective method here; this isn’t well understood.

There are other anti-seizure medications, but those are usually not recommended in these cases because the seizures are benign and the medications have side effects.

Does it predict long-term health risks?

There are two primary concerns. One is that these seizures might cause long-term damage. There are a number of small studies that estimate whether children with simple febrile seizures show lower cognitive performance either immediately or shortly after, and show that they do not. One very large study uses data from 18,000 military conscripts in Denmark and finds no relationship between test performance and having been hospitalized for a seizure during childhood.

The second concern often raised is a possible link with the development of epilepsy. The largest study of this question comes from 1976; that study shows a slight increase in epilepsy risk for children who have had a febrile seizure versus those who have not. The risks are, however, small in both cases (1% versus 0.5%), and the increase in risk is correspondingly limited.

Complex febrile seizures

A complex febrile seizure lasts longer than 15 minutes, has a “focal onset” (shaking is limited to one side of the body), or occurs more than once in 24 hours. These represent about 20% of febrile seizures.

With a complex febrile seizure, there are more concerns about possible longer-term risks, including neurological damage. It is important to note that, still, in most cases, these do not presage long-term health outcomes.

With a complex seizure, the details matter more, and your doctor will be an extremely important source (as they always are). Children with a complex seizure are more likely to need admission to the hospital because of a concern about additional seizures over the immediate period. It is also not uncommon to have ongoing weakness in some areas if a seizure was focused on one side.

How common are recurrences?

Following the acute phase, the risk of recurrence is similar to the case of simple febrile seizures — a similar overall risk and similar predictors. In cases of complex seizures, which last longer, parents may sometimes be given a home treatment (a benzodiazepine) that can be administered if there is a recurrent seizure that lasts longer than five minutes.

Does it predict long-term health risks?

The biggest worry with complex febrile seizures is that they suggest an increased risk for other seizure-related disorders, including epilepsy. Children whose first febrile seizure is complex have a risk of epilepsy of about 9%, versus 0.5% in those without seizures. Even with this, the vast majority — over 90% — of children with complex febrile seizures do not develop epilepsy.

Related to this, children with complex febrile seizures are also at higher risk for other seizures not associated with a fever. For this reason, sometimes anti-seizure treatments are considered (there are several drugs that may reduce seizure risk). This is not a standard treatment, however, since in many cases, the benefits may not outweigh the risks.

Overall, if your child has a complex febrile seizure, there will be more questions to answer. Rather than trying to answer them here (impossible), it may be easier to think about what these key questions for your doctors are. Specifically:

- What other tests do you recommend we do (options include a lumbar puncture, an EEG, an MRI, or possible genetic testing)? Most of these are not done, but they may be considered, largely to rule out other explanations for the seizure.

- What should we be watching out for at home?

- Do you recommend we consider having a treatment on hand at home if they have another seizure?

- Do you recommend routine anti-seizure medication?

There are unlikely to be clear answers to these, but they are a starting point for discussion.

What should I do if my child is having a seizure?

During a febrile seizure of any type, what you should do is relatively simple.

- Lay your child on their side on the ground or a surface where they cannot roll off.

- Do not restrain them.

- Make sure there is nothing sharp around that could hurt them.

- Watch for signs that they are having trouble breathing (specifically, turning bluish). This would be a sign to call 911.

- If you can, record how long the seizure lasts.

Closing thoughts

Let’s end where we started. Nearly all of the time, a febrile seizure will be harmless for your child and will not be a harbinger of issues later. Further, children grow out of these by around age 5, so it isn’t something you will be worrying about or dealing with beyond that. Having said that, for parents, it is extremely scary. Give yourself grace to deal with whatever your reaction is, noting that, like most things in parenting, you’ll be living with this long after your child has forgotten about it.

The bottom line

- A febrile seizure is a seizure that occurs in a child 6 months to 5 years, accompanied by a fever above 100.4 degrees. They are common: an estimated 2% to 4% of children will have at least one.

- Although febrile seizures occur as a result of a fever, lowering the fever with medication does not reduce the risk of seizure.

- Simple febrile seizures, which make up about 80% of febrile seizures, are short (usually under five minutes), generally harmless, and do not signal serious long-term health problems. Recurrence is fairly common — about one-third of children will have another.

- Complex febrile seizures, which make up about 20% of febrile seizures, last longer than 15 minutes, affect one side of the body, or recur within 24 hours. While most children recover fully, these seizures carry a higher risk of later epilepsy. Despite these concerns, over 90% of children with complex febrile seizures do not develop epilepsy, and long-term outcomes are generally positive.

- If your child is having a febrile seizure of any type, do not restrain them; lay them on their side and ensure they are physically safe (make sure they are on the ground or a surface where they cannot roll off and that there is nothing sharp around them). If they are having trouble breathing, call 911.

Log in

It’s a crazy thing to think about, but if you think your child is having a seizure record a video of it! This is immensely helpful to the neurology team! Even just 10 seconds can be a huge help.

-Mom of a kiddo with medical complications who has had 2 complex febrile seizures

A note to parents that seizures don’t always present with typical shaking symptoms. My son had an absence seizure where he had a blank stare and was unresponsive for almost five minutes before slowly coming out of it.