If you are a fan of endurance sports (who isn’t!), you’ve probably heard talk about something called “sodium bicarb.” Some elite athletes swear by it, crediting it with driving their performances to new heights. And if you, yourself, are into these activities, you may be wondering: Is this something I should also be taking?

And even if you weren’t before, perhaps having read that first paragraph, you’re thinking: Why would baking soda help with running?

Here: What on earth am I talking about? What is sodium bicarbonate, and why are people taking it in high doses? If you’re an athlete, what does the data say about whether this works and whether there are downsides? And, finally, a detour into whether this might also be a hack for labor.

What is sodium bicarbonate?

Sodium bicarbonate (also referred to as “Bicarb”) is the scientific name for baking soda. It has long been suspected that consumption of baking soda could impact athletic performance issues by raising what is called “the lactate threshold.”

When you exercise, your muscles use glucose through a process called glycolysis. This process, among other things, releases hydrogen ions. At lower exercise intensity, these hydrogen atoms are processed by your mitochondria. However, at high exercise intensity, your oxygen consumption cannot keep up, and these hydrogen ions start to accumulate in your muscles.

This accumulation makes your muscles more acidic, and that interferes with functioning in various ways, including lowering your ability to generate force and limiting enzyme reactions. This all makes you feel very fatigued and often have a kind of burning muscle sensation at high exercise intensity. If you have ever run very hard for a medium distance and started to feel your arm muscles ache and burn, that’s the sign of this hydrogen buildup.

People often call this the “lactate threshold,” but that name is somewhat misleading. During this same process, at high exercise intensity, one of your muscle byproducts is converted to lactate. So while the hydrogen ions are rising in your blood, lactate levels are also rising. However, the lactate isn’t what contributes to fatigue (in fact, it acts as a buffer to some extent). Because it was more common to measure lactate in the bloodstream, people had the impression that it was the lactate that drives fatigue. Hence the name “lactate threshold.”

Hitting this threshold — whatever you call it — is a performance limiter. This is most commonly an issue in shorter, more intense exercise bouts — think the 800 rather than the marathon. Interval training can raise the intensity level before you hit this threshold, and overall, aerobic fitness can improve how fast you can go before you hit this intensity level. But neither of those eliminates the threshold problem altogether.

How does sodium bicarbonate work?

In the blood, sodium bicarbonate breaks down into sodium and bicarbonate. The bicarbonate ion is negatively charged, and it attaches to positively charged hydrogen ions, making carbonic acid. Carbonic acid quickly breaks down into carbon dioxide and water, which you breathe and sweat out.

Thank you for coming to high school biology! My point is, if you consume a lot of baking soda and have a lot of bicarbonate ions floating around in your blood, then you’ll (in theory) be better able to deal with the buildup of hydrogen ions, and they may get removed before they start to cause your muscles to get tired.

In a more practical sense, the idea is that if you consume a large amount of baking soda, you’ll be able to push harder at higher intensities without this intense muscle fatigue kicking in.

This basic idea that baking soda could have this impact has been known for a long time. The problem: you need a lot of baking soda if you want to get any benefits, and if you eat a lot of baking soda, you’ll feel like garbage. It will react with your stomach acid to produce bloating and all kinds of other GI issues. Not to put too fine a point on it, but you cannot perform in your race if you cannot leave the porta-potty.

The reason we are hearing more about this now is that recent advances in sports nutrition have made consumption a bit more possible. There are a number of products that combine small baking soda tablets with a gel-like substance. The gel coats the tablets, and the gel itself only breaks down with the pH of the small intestine, allowing the sodium bicarbonate to transit the stomach without breakdown and, hopefully, lower GI issues.

A number of companies make products like this. The typical approach is to take a large dose — perhaps 0.3 grams per kilogram of body mass — 60 to 180 minutes before the performance activity.

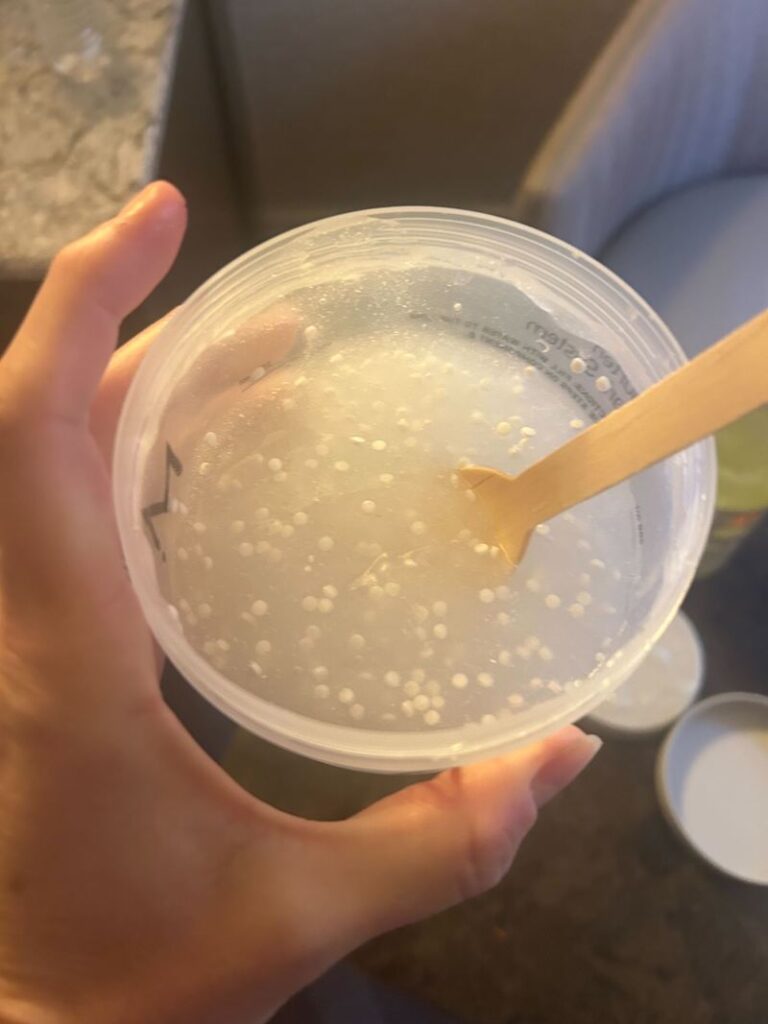

To show you practically what this looks like, here is a photo of me eating a bowl of gel full of sodium bicarbonate tablets. It is exactly as delicious as it looks.

What does the data say about performance?

As a first step to this question, we can ask whether the chemical reactions work as expected here. The answer is, yes, they do. In one detailed randomized experiment, researchers showed that the hydrogen ion concentration in the blood was lower with sodium bicarbonate supplementation than with a placebo. Interestingly, they showed that lactate was higher, which may indicate work to higher intensities in those groups. Based on this, you’d expect the threshold for exhaustion to be raised and performance to improve.

Looking more directly at performance, a review of randomized studies suggests that sodium bicarbonate improves time to exhaustion in trials. A concrete example: in one study of eleven elite male cyclists, researchers showed benefits in an ending sprint even after a longer endurance activity. Translation to you: at the end of that 5K, Bicarb might be the answer to sprinting past that guy in front of you.

The data here is not universal in pointing to benefits. As this review points out, there is variation across studies and across people. Better-trained athletes may benefit less. There is some evidence that women may need longer for this to work; an hour may not be enough. The International Society of Sports Nutrition comes down on the side of sodium bicarbonate improving performance across a wide variety of athletic activities (including running, cycling, and even martial arts). However, they do say the benefits are largest in exercise ranging from 30 seconds (this would be, say, a deadlift) to 12 minutes. And yet many people are using this for much longer races.

So while we can say that on average there are benefits, this isn’t a miracle drug. It’s also worth saying that the evidence at this point is still extremely limited. These products are new, expensive, and not widely used even among elite athletes. More information is needed.

Are there downsides?

Well, yes. Despite the advances in delivery mechanisms, GI distress is common in people who take these. You see that in studies, and it is clear why it would happen. This distress can take many forms — bloating, nausea, vomiting, and, especially, diarrhea. Before the new delivery systems, you were virtually guaranteed to get diarrhea if you consumed a lot of baking soda. After, it’s less common, but it still happens to many people.

The other issue is that you want to make sure you drink enough water to counteract the sodium. For someone of 140 pounds, the recommended dosage of sodium bicarbonate delivers about 5,000 mg of sodium. That’s twice your recommended daily limit, so it’s important to balance out with water.

This stuff is also expensive. Purchasing the baking soda and gel concoction from Maurten (they called it their “Bicarb system”) is about $15 per dose. It’s not exactly super shoe prices, but it does feel high for … baking soda.

For all of these reasons, this isn’t something most people, even most elite athletes, will use outside of races or the occasional hard training session.

Some anecdotal evidence

With limited formal data, a lot of what we have about athletic use of sodium bicarbonate is based on anecdotes. Some elite athletes have reported using it, and their reactions are mixed. Professional cyclists report using it for some of their races, largely those with a sprint component.

I did a highly non-representative survey of my Instagram followers on this topic, which resulted in a small number of responses from people ranging from recreational to elite athletes, across running, cycling, and trail running. On average, people reported positive experiences, but the overall feedback was fairly mixed. For longer distances, in particular, GI distress seemed to dominate the perceived performance value. And one person did report an incident of what she called “Bicarb cholera.”

This is consistent with the sense I get from talking to running coaches and others. Some of their athletes like this, some do not, and there’s much less consistent support for use at longer distances.

Does Bicarb help with labor?

Childbirth is like a marathon, right? So … useful there too? Maybe! There are several randomized controlled trials (see here and here) showing that giving women sodium bicarbonate when labor is stalled increases the chance of a spontaneous vaginal birth (that’s a birth without forceps or a vacuum). The underlying theory is the same as in the sports case. Labor requires extensive muscle contractions. If it lasts a long time, the muscles fatigue, and they do not work as well. Data shows that high amniotic fluid lactate levels predict stalled labor.

Supplementation with sodium bicarbonate may improve muscle functioning, making spontaneous vaginal birth more feasible.

These trials are both small, but a protocol was just published for a new trial in Norway, which will be much larger and look at the impact of supplementation on the overall success of labor induction.

We will have to stay tuned to see how this turns out. If it works, I’m planning a ParentData-Maurten collab where we sell the sodium Bicarb system in a commemorative ParentData bowl.

The bottom line

- Sodium bicarbonate (also referred to as “Bicarb”) is the scientific name for baking soda.

- Consuming a lot of baking soda may help improve athletic performance by making it possible to push harder at higher intensities without intense muscle fatigue kicking in.

- New gel-coated versions of baking soda are designed to make it possible to get the performance benefits without as many negative side effects (mainly GI distress).

- Research suggests that consuming these products can modestly improve short, high-intensity performance by delaying fatigue, though results vary by person. The evidence for Bicarb improving both athletic performance and labor is still limited.

Log in