My fourth book, The Unexpected, is out on April 30. This book would have been impossible without my extraordinary co-author, Dr. Nathan Fox. I am, as a rule, not much for group projects, but Nate is a dream collaborator — smart, thoughtful, honest, and the only person who writes back to email faster than I do. In this episode we talk about the new book, what we each want people to get from it, and why we loved working together. And my producer, Tamar, comes on for a few pointed questions. Enjoy!

Here are three highlights from the conversation:

Who should read The Unexpected?

So for me, it’s part of what I didn’t expect you to bring to the table. And I do think it’s probably among the strongest pieces of the book.

And number one, if someone is fortunate enough to never have had a pregnancy with a complication — which is actually unusual, but let’s say that’s the case — everyone knows someone who had a pregnancy with a complication. Everybody knows someone. It may be their sister, their friend, whatever. And I think that this book is also written in a way to help people understand what their circle of people have gone through, and to just give an appreciation for that, and what they’re thinking, and what their fears are, and what their concerns are.

And I think also just in general, since the complications are so ubiquitous we’re talking about — this is not crazy things that no one’s ever heard of: we’re talking about miscarriage, preterm birth, bleeding. I mean, things that so many people have in pregnancy and people talk about, this really gives people an understanding of them or of pregnancy at a much higher level. So even someone who’s never been pregnant or is never going to be pregnant, it’s sort of interesting in that sense to understand it.

And I think, on the deepest level, what I was trying to bring to the table is also even for someone who’s not, literally never, going to be pregnant — talking about a single guy, whatever it is — I try to get into that concept of what’s happening when you’re with your doctor, and why it’s so complicated and why it’s so rich. It’s a relationship. It’s not like ChatGPT, where you plug something in and you get back a response. It involves personalities, it involves emotions, it involves nuance. And although this is related to pregnancy, obviously, and that’s sort of the framework we use, the principles are very broad.

What does shared decision-making look like between a doctor and a patient?

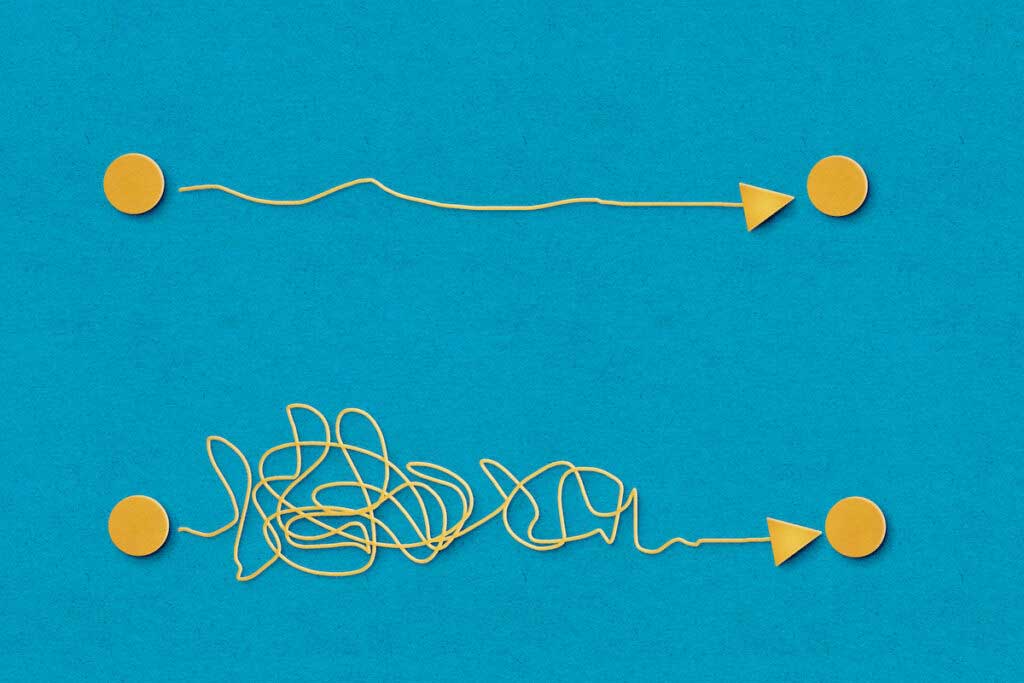

And so the best part of shared decision-making is she brings to the table her expertise about herself. And I bring to the table my expertise about the medical side. And we try to use both of those expertises together to come up with the right answer for what to do for her to individualize it. That’s how it should be. But what ends up happening is, people say shared decision-making. And then what ends up happening is the doctor says, “Well, you can do A, B, or C, and it’s your choice.” And some people are like, “Great, I get to choose.” And other people are like, “What the hell? I don’t know. How am I supposed to know?”

Literally, if my plumber said to me, “Well, we could use copper pipes or we can use plastic pipes; what do you want?” I’d be like, “What do I look like? A plumber? I have no idea. You tell me what’s better.” Now, if the plumber said to me, “From my expertise, the copper pipes,” and this may be false, but “the copper pipes are more expensive, but they’re going to last 10 years. Whereas the plastic pipes are less expensive and they last three years.” And I know how much money I have, whether I’m leaving the house in three years, how much it bothers me to have a plumber come back. And so that’s shared decision-making. But if you just said, “Here are your choices; let me know what you want,” that’s not shared decision-making, and that’s what ends up happening a lot. And it’s very frustrating both for doctors and for patients when it’s not done in the ideal setting or the ideal way, I would say.

How much time can those conversations take?

And if you come in better-informed with a sense of your questions and a sense of what you’re trying to get out of the visit or what the choices even might be, it can make those conversations more productive. And I think this book is really about: let’s get enough background knowledge and come into that conversation in the right way.

Full transcript

This transcript was automatically generated and may contain small errors.

And so a few months later, I found myself sitting at lunch eating pita and hummus across the table from Dr. Nate Fox. And indeed we did see eye to eye on many things. And beyond that, we really liked each other. And Nate and I have stayed in touch since then. We wrote a paper together in a journal and a couple of years ago when I thought about writing a fourth book about complications after pregnancy, I knew who I would call and I called Nate.

And I remember walking around outside on the phone pitching him in this idea, “Hey, let’s write a book together about pregnancy complications. I don’t know exactly what it’ll look like. I don’t know exactly how it should be structured. I don’t know exactly what should be in it, but I know that you’re the person I should write it with.” And Nate is always game. Without asking any more questions he said yes.

And now on April 30th, 2024, that book is out. The book is called The Unexpected: Navigating Pregnancy During and After Complications. And I invited Nate on the podcast, this is actually his second time on the ParentData podcast, to talk about our book, to talk about why we like to work together and to answer some of the questions that people have asked us about navigating complicated pregnancy.

In this conversation, Nate and I will talk about some of the complications in the book. We’ll answer some questions, but we’re also going to talk about some bigger picture issues. One of them is how do you have good conversations with your doctor? How do you talk about especially these hard things when you’re both bringing different kinds of expertise to the table? We’re also going to talk about risk, and how we communicate about risk, and why it’s hard to help people understand what a number like 1/3 or 1% means. Nate and I have different takes on exactly how to do this, but just like working on the book together, I feel like we got to a good place.

Nate’s one of my favorite people to talk to. I call him all the time. And I’m delighted he came on this podcast, but even more delighted to have him as a partner in this book. So I hope you enjoy this conversation. After the break, Dr. Nathan Fox.

Did you work on group projects in middle school? That was my MO.

And so it’s a little intimidating to work with someone who’s so good at this because I’m not down on myself. I’m a lovely person. I think I’m a bright guy. I’m a good doctor. But I’m not a writer, it’s not what I do. And so it’s a little intimidating to go into a process with someone. And I’m like, oh my God, I’m going to be terrible. I’m going to suck. I’m going to hold her back, and this or that. But whether I did or didn’t, you were very gracious. And you’re always very encouraging, and did not make me feel that way either because I didn’t deserve to feel that way or because you were kind enough not to make me feel the way. I don’t really care. Either one is fine. But it was really a delight.

And I could say that I’ve actually always toyed around with writing a book. Years ago I said, “I want to write a book.” But I mean, well, I’m not going to write a book. So I thought I would and that was one of the things I really, really wanted to talk about in a book was not so much like nuts and bolts medical type books. I’ve written medical chapters before for textbooks, but not that. That’s not writing, that’s horrifying. But writing to people who see doctors to try to give them an insight as to how do you know what to do, what to ask? How do you know if your doctor’s any good? How do you know if this is productive or not?

Because I mean, if your doctor’s nice, and you know if their office is clean, and you know if they run on time, and you know if their billing department’s annoying. You know those things. But you have no idea if your doctor’s any good. You could see a diploma on the wall, but the correlation between that and a good doctor is very minimal. And it’s hard, legitimately. Listen, I’m also a patient and my wife’s a patient, my kids are patients. How do I know if our doctors are good? It’s very, very hard.

And so that was something I always wanted to do. And when this project came along, it actually worked out perfectly because it’s what we both wanted to do from different angles. And so I think one of the reasons it was really fun in that sense for me.

And what the book does is there’s some sort of general material at the top to try to help people think about what kinds of information they should have out of their medical records and how to navigate their way into that. And then there are a series of chapters which, in which first there’s Emily talking about the answers to many of the questions I get, which are, will this happen again? What’s the risk of recurrence? What kind of treatments are there? Can you help me just understand what this complication is?

And then there’s your part of the chapter which is about how do I have a conversation about this with my doctor? In the case of many of these complications, probably all of them, there’s not one answer. It’s not like if this happened, for sure this is what we’ll do next time and everything will be fine, and thanks for the data. A lot of it is about the nuances of a particular case and just the details of how to move through it. And so the thing that I think we get out of your parts of the book are just how to navigate those conversations.

And I will say, I had a conversation the other day with someone who works in birth trauma and who was very influential for me in thinking about writing this book. She said, “I started reading this book and I thought this is going to be kind of like Expecting Better but for complications. And this is going to be a great resource. And I’m glad that this is going to be available.” And then she said, “But actually the book is so much better than that because Nate’s parts are so great. And your parts are fine, I expected them to be like they are. But this additional piece is the most important thing in the book.”

So for me, it’s part of what I didn’t expect you to bring to the table. And I do think it’s probably among the strongest pieces of the book.

And number one, if someone is fortunate enough to never have had a pregnancy with a complication, which is actually unusual, but let’s say that’s the case, everyone knows someone who had a pregnancy with a complication. Everybody knows someone. It may be their sister, their friend, whatever. And I think that this book is also written in a way to help people understand what their circle of people have gone through, and to just give an appreciation for that, and what they’re thinking, and what their fears are, and what their concerns are.

And I think also just in general, since the complications are so ubiquitous, we’re talking about, this is not crazy things that no one’s ever heard of. We’re talking about miscarriage, preterm birth, bleeding. I mean things that so many people have in pregnancy and people talk about, this really gives people an understanding of them or of pregnancy at a much higher level. So even someone who’s never been pregnant or is never going to be pregnant, it’s sort of interesting in that sense to understand it.

And I think on the deepest level, what I was trying to bring to the table is also even for someone who’s not, literally never going to be pregnant, talking about a single guy, whatever it is, it really, I try to get into that concept of what’s happening when you’re with your doctor, and why it’s so complicated, and why it’s so rich. It’s a relationship. It’s not like ChatGPT where you plug something in and you get back a response. It involves personalities, it involves emotions, it involves nuance.

And although this is related to pregnancy obviously, and that’s sort of the framework we use, the principles are very broad. And that’s sort of when I was thinking it’s not just nuts and bolts, it’s sort of high level what’s happening in these meetings. And this would be, I would think, relevant for anybody about to see a doctor for a question. How do I think about it? How do I talk about it? What am I looking for? How do I know if they’re answering my questions? Because that’s like the golden question out there.

I don’t know. I feel like it’s kind of interesting for the two of us to write that because that is effectively what we try to do working together, is recognize that you have a set of expertise that I don’t have and I have a set of expertise that you don’t have, and we’re trying to bring them together to work as a team.

And so the best part of shared decision-making is she brings to the table her expertise about herself. And I bring to the table my expertise about the medical side. And we try to use both of those expertise together to come up for the right answer for what to do for her to individualize it. That’s how it should be. But what ends up happening is people say shared decision-making. And then what ends up happening is the doctor says, “Well, you can do A, B or C and it’s your choice.” And some people are like, “Great, I get to choose.” And other people are like, “What the hell? I don’t know. How am I supposed to know?” Like if my plumber said to me-

But anyway, I ended up in the hospital with a laceration in my head. And in that moment, my expertise in my own feelings about my head and so on is really not relevant. The question is somebody needs to figure out if you have a skull fracture or not, and that’s the doctor’s expertise and you kind of have to defer.

And then there are settings in which it’s almost entirely about patient preferences. One of the ones we’ve talked about various places is what kind of genetic testing people want. So if you’re pregnant, you want some genetic testing, that’s really a lot about what would you do with that information, what are your feelings about the results out of that? And the doctor can provide information about what you learned from the test, but ultimately the patient preferences really win.

And then there are many things in the middle where there’s a combination of expertise about your medical situation and what’s possible with what does patient preference look like.

And there has been a pushback against that, I think in a good way. But now I think the pendulum is sort of going the other way where people are being trained in medicine, patient autonomy, he should make the choice, she should make the choice, present them with options and they’ll choose.

But neither is really correct. It depends on the circumstances. And so if the patient’s hemorrhaging, I’m not going to say, “Which medication would you like for me to help you stop hemorrhaging?” Then I’m an idiot and I’m a terrible doctor. But for things like genetic testing, if I tell her, “You’re going to do A, B and C,” that’s also really not good.

And so you have to know the situation. You got to read the room in a sense. You have to read the room. What does he or she want? Do they want you to be a little bit more tell me what to do versus give me choices? And what is the decision that we’re making call for?

This is something we talk a lot about in the book. A little bit different than some of the other complications in the book because a cesarean section is not sort of properly a pregnancy complication the way preterm birth or preeclampsia is. But it is something we wanted to include because many people wonder about this in a subsequent pregnancy when they’ve had a C-section the first time.

So let’s do a little, Doctor Nate. So I come in, I say, “I had a C-section in my first birth. I’m trying to decide about this next birth.” What are you asking me?

Next is what were the circumstances of your C-section? Why did you have the C-section? Was it because you had a six-pound baby and pushed for eight hours and the baby didn’t come out? That’s a little bit, doesn’t sound as good for your future prospects, although it’s not definitive. Versus, “I had a totally healthy pregnancy, but since it was twins and they were both breached, they said to do a C-section.” And no, that’s not so much related to the risk in the next pregnancy, but the likelihood of success in the next pregnancy, meaning with success being defined as a vaginal delivery. Although obviously success is healthy mother, healthy baby. But we’re talking specifically about this.

So for me, based on her history, based on maybe reviewing her records, maybe an examination of her, maybe an ultrasound, whatever, some tests, what I bring to the table is here’s the likelihood that if you tried you would be successful. Is it 50%, 70%, 90%? Whatever it is. And what is the risk to you if you try it? Is it in that 1% range or is it much higher? That’s what I bring to the table.

But what she brings to the table is, well, what does she want? And so I always ask her at the beginning of this, in addition to those questions, I say, “What are you looking for? What is it you’re trying to get here? Are you looking to try to have a vaginal delivery? Are you looking for a repeat C-section? Do you have no idea and you want to sort of learn about each of those?” And I need to see what she wants and what are her fears. And I’ll have the same sort of clinical circumstances, let’s say.

And one person says, “I really, really want to try VBAC, and I’m willing to accept certain risk and certain likelihood of success.” And someone else is like, “I want no part of that. I want to a repeat C-section.” And those are both good decisions, in my opinion. So you have the same facts on the table from my end, but they lead to different decisions because the facts on the table from her end are different, what she wants.

And vice versa. I could have two women who want the same thing, but they’re going to have different numbers on my end. And one of them I’ll say, “You have a 50% chance of success.” And the other one, “You have a 90 plus chance of success.” And so then they may decide differently.

And so that’s really how shared decision-making is supposed to work. And unfortunately it doesn’t, either because the doctor’s not doing their job by getting the right information or inquiring what does she want in getting her opinion, or because potentially it’s trying to be done but let’s say the hospital doesn’t have an option for VBAC so it’s irrelevant almost in a sense. And there’s a lot of stuff that goes into that.

But that’s what we’re trying to get at this book, to help people create those kinds of conversations or find someone who can have that conversation with you so you can come to a good decision.

But just for example, I’ll say, “How many kids do you want to have?” If she says, “Nine,” then the second delivery, whether it’s a vaginal or C-section, is going to have a lot more implication for her future health. Because if she has her second, she’ll end up with nine C-sections. Where if she delivers vaginally, it might be one C-section followed by eight vaginal birth.

But short of that, it could be very, very short. Sometimes it’s very, very long. Sometimes we’re working through what does she want? What are the risks? What does this mean? What does that mean? What would happen if? What would happen if? And that’s fine. And it’s rarely not that long if everyone comes to the table with a mutual of understanding of what we’re trying to do here.

There are other conversations that are a little more time specific like genetic testing. And I’ll tell you that when I, I lecture a lot about genetic testing, and it’s one of the things I talk about. And so many people they say, and it’s true, “This is so hard. This is such complex stuff. No one understands this. How could you possibly have a conversation with your doctor, or doctor have a conversation with patient, and put them at a level that they can understand this?” And the answer is they can’t. That’s true. You need an hour, let’s say. But if someone has a basic understanding of what we’re talking about and the person who’s doing the counseling, the doctor, the genetic counselor really is focusing on what we’re trying to answer, it doesn’t take that long because you can sort of hone in on the question.

Like, “If your risk were 1%, does that number seem scary to you or reassuring to you?” It’s a very simple question that people can answer. And I’ll tell them, “If all your testing is normal, your non-invasive testing, your ultrasound, this, your risk of a baby with Down syndrome is very, very low. One in 10,000. But your risk of any genetic condition is 1%. Does that number reassure you or scare you?” And if it reassures you get up and leave, you’re done, have a good day. Whereas if that terrifies, you should be thinking about a CVS or an amnio.

And that’s a very straightforward question that most people can answer. Not everybody. Some people are like, “I don’t know how I feel about 1%.” “Fine, think about it, get back to me.” But it requires a lot to get to that question. And so again, it’s on the doctor, it’s on the patient, it’s on everybody to try to make these more productive. And I hope that this book is very helpful with that.

And I always say to them, “When you go for a VBAC, you’re going to get the best or the worst. You’re not going to go to the middle. So are you the type of person who would roll the dice a little bit, so to speak, to try to get the best option, knowing it may backfire?” again, not backfire like die, but whatever in terms of maybe overall outcome. “Or are you the type of person who really, I’d rather just do the middle of the road?” And people can wrap their heads around that. They know who they are.

And so we try to help people make these decisions by framing the questions in a way that if you’re this type of person, you’re likely to go this direction. Whereas if you’re this type of person, you’re likely to go this type of direction. And that I found to be helpful over the years to try to let people, give them that context to make complicated decisions.

All right, so let’s test this out for a minute. We’re going to see where the rubber meets the road. I’ve invited Tamar, my producer, in to ask Nate and I some questions.

So the question is what is the chance of that? I believe the population frequency depends on its ancestry, but let’s say it’s one in 50, 2%. So the chance that you’re a couple that both carry cystic fibrosis is 2%. And if he carries cystic fibrosis, then each of your kids has a 25% chance of having it, which you could either get pregnant and test and find out, or do IVF and test the embryos and only put in embryos who don’t have cystic fibrosis. All that’s available to you. But I’m glad you’re doing the testing, it’s good to know. But minimally is what I would say in terms of how much to freak out.

And when you undergo advanced and comprehensive genetic screening, more than 50% of people will get back a positive quote, unquote, “abnormal result,” meaning you have a mutation that’s very, very common. It’s not unexpected, it’s not a problem, it’s not a health issue. It’s not any issue whatsoever unless you happen to be procreating with someone who has the same mutation, which is unlikely.

The evidence, theoretically it seems like this could help do that kind of detection. In practice, the evidence to support this as an important method for preventing stillbirth is quite weak. And part of the issue is that stillbirth, while more common than many people think, is still very rare. And so it’s very difficult to run a large trial that would actually detect changes in stillbirth just because the overall prevalence is low. And so any changes, you need a lot of data to detect them statistically.

So I think this is one of the cases where it actually depends a little bit on how someone’s going to kind of come to it emotionally. So for some people, this is very reassuring and it’s like, “I’m going to do this, I’m going to put it on my calendar, I’m going to do it every day.” That’ll sort of be a positive experience. And for some people it’s super anxiety-provoking. We do get more visits to doctors as a result of this because people want reassurance.

So I’m not sure there’s 100% answer to whether this is the right thing for everybody.

So I don’t typically recommend kick counting as a routine, but I tell people if they feel their babies moving abnormally one day… Because most people know their babies. Some babies are reactive, some babies are less. Some babies move at night, some babies move in the morning. Babies have personalities just like adults do. And so if you think there’s a change and something’s unusual, and you’re concerned, then I will say, “All right, lie down, close your eyes, focus on the baby. Wait 30 minutes. If you feel three movements, it’s okay. And if you don’t, let us know.”

But as a routine, I don’t, anyone who’s high risk enough for stillbirth I have them come to the office once or twice a week for formal testing. Whether it’s a biophysical profile or a non-stress test so we can really get something with data on it and something really can see. Whereas if someone was at low risk for stillbirth, I generally just say, “Just keep an eye on your baby. And if everything seems normal, you’re good to go.”

So Tylenol, you can also google some bad things about Tylenol, but basically the overwhelming evidence is that Tylenol is safe. And the studies that seem to scare people about Tylenol are very complicated because it could be the reason someone took Tylenol, which is usually fever, illness, this or that. So Tylenol is separate.

Ibuprofen, which is Motrin, which is Advil-

But if someone needed it at 18 weeks, they could take it. And we tell them this, and then so we sort of do give it to people for certain circumstances. But yes, later in pregnancy, it becomes definitely don’t take it later in pregnancy. But that’s, exactly when, exactly how much, it’s a little bit complicated, which is why there’s more of a blanket statement not to take ibuprofen because it will become dangerous. But there are a lot of nuances to that.

Listen, are there doctors who make recommendations because it’s easier for them than the patient? I’m sure. I’m sure they exist, right? I don’t know how many doctors there are in the United States, a million? I don’t know what the number is. Many, many, many doctors. And I’m sure there are ones that make recommendations that are not in the best interest of their patients.

I would say in my experience of knowing doctors, talking to doctors, meeting doctors or working with doctors, very rare. It doesn’t work like that typically. And I would say that especially in the field of obstetrics, the way things have evolved, you rarely have that solo practitioner who’s deciding between a tee time and a birth.

So take my schedule for example. If I’m covering the labor floor, I’m on the labor floor from 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM. Makes no difference to me whether someone has a vaginal birth or a C-section, from my convenience. Whatever’s best for her is best for her. And similarly, I’m being relieved by someone at 7:00 PM who is fresh, and slept, and capable, and had dinner, and is someone I trust. And so whether someone has a C-section at 6:00 PM, or we wait and they have it at 9:00 PM, or they deliver vaginally overnight, doesn’t matter to me. There’s no upside or downside to me.

So I think nowadays, that of behavior, if it existed or to what degree it existed, must be much less because there aren’t the same time pressures on obstetricians that there may have used to be.

But I think that definitely doctors sometimes consciously or subconsciously worry about, well the chance of something going wrong is very low and medically it’s probably okay to continue if she wants to, but if something were to go wrong, it’s not going to look good on paper and I’m going to be in big trouble. And either that means I’ll get sued or the hospital’s going to come down on me because they’re going to get sued, so they’re going to restrict my privileges. And again, I’m not saying that to complain. It’s a reality of the system and it’s hard.

I don’t know what the solution is, but that is probably a more prevalent factor than the doctor’s tee times, or show tickets, or dinner reservations, or whatever the doctors are supposedly doing in high society that the regular people aren’t. So we’re probably going home to our second job is what we’re doing.

So I had a last topic I want to talk about because I think it is something that we don’t agree on, and there are very few things like this.

And you came into this, I think, with an idea that there are three categories of risk that you like to explain to people. There’s probably this won’t happen again. Most of the time this is pretty idiosyncratic, so it’s probably not going to happen again. It might happen again, but you don’t really know. Or you should assume it’s going to happen again. And if it doesn’t, you’re lucky. I think is how you put it. So you’re kind of like pooh-poohed my precision around risk.

I think that there’s two issues with trying to get that precise. Number one, the research we have in almost all of these aspects is so limited that the difference between 16% and 21% is usually nothing because the brackets around them are wide enough that it really doesn’t, there is no actual difference between those numbers, which you understand better than I do, but sort of statistically. So that’s one issue.

The second is I don’t think most people think like you think. So I think there are people, and I certainly taken care of them, come across them, have some in my family or this, who they’re like, “No, I want to know is it closer to 16 or closer to 21?” And fine, I’ll tell you, God bless. We’ll go to the decimal point. However many sig figs you want, we’ll go there, no problem.

But most people don’t think like that. Most people when they’re thinking about risk, they categorize in their brain like high risk, low risk, medium risk, where am I? And so I usually break it down, again, based on the risk. Into something like less than 10, 10 to 50, or more than 50. Again, it depends on sometimes all of them are under 10 and it’s like less than one, one to five, five to 10. It depends on the…

But try to give them a sense so they can wrap their head around the statistics. Because most people, the average person is functioning at, I don’t know, a middle school level when it comes to statistics. That’s not an insult. That’s like high-functioning people who are very bright and working in the world, that’s the level of statistics they’re usually working at. The exception are the people who are very, very into data and want to know the exact decimals and God bless them. But they’re the exception, they’re the outliers, I would say.

And so for me, if you get into very, very precise numbers on people, with people, you lose them, in counseling. Now with reading, it might be different because it’s a reference versus a conversation. They hear 17%, what does that mean to them?

And also the other thing is people think about math differently. So I always have to say those numbers twice. I’ll say, “Your risk is 30%. Your risk is about three out of 10, about one out of three.” You have to say it in so many different ways because people hear things differently. Some people don’t get percentages. When I tell people one in 10,000, some people don’t get what that means. And again, not that they don’t understand it, it’s just they’re hearing it, and they may be more of a verbal learner and you have to write something down or, it’s fascinating. The human brain is fascinating. And so we see all-comers and that’s sort of what I was getting at. Not so much that it doesn’t matter, but it’s usually not practical.

And I said, “Think about it. You can close your eyes, and flip a coin and make this decision. And whether the coin lands heads or tails, 99 plus percent of the time, you’re not going to miscarry and you’re going to have a healthy baby.” I said, “No matter what, right? If you do a CVS, 99 plus percent of the time, you’re not going to miscarry. You’re going to have a healthy baby. And if you don’t do a CVS, 99 plus percent of the time, you’re not going to miscarry. You’re going to have a healthy baby. How often in your life do you get to make a decision that’s important to you where 99 plus percent of the time it’s going to work out no matter what you do?” I said, “So don’t lose too much sleep over this.” I said, “Go with your gut.”

If it’s 1% versus 8%, then it’s different. But when it’s really, really small numbers, it doesn’t matter to the individual, it matters to the population. And so I try to help them not worry too much about the decision because it won’t matter for almost everybody. And they have to do, I say, “You have to sleep at night. So whatever’s going to make you sleep at night, that’s what you should do because you have to live with yourself the rest of the pregnancy. So pick that one.”

So again, you have to break it down in a way that’s sort of manageable for people.

But then also when we decided to write this book, like I said, you’re a well-known author. You do this, you’re very, very good at it, you’re very successful. A lot of people listen to you. And you could not have been more gracious in doing this in a way that made me feel like a partner. Even partners, whatever you want to say it is, that we work together on this and I really, really enjoyed it. I learned a tremendous amount from you and from the process. I’m very proud of the book. Really, I’m proud of it. I think what we did was great. I think it’s going to hopefully help a lot, a lot of people. I am going to, again, display it proudly. And it’s really something I’m going to cherish that we did for a long time. It’s great.

ParentData is produced by Tamar Avishai, with support from the ParentData team and PRX.

If you have thoughts on this episode, please join the conversation on my Instagram @profemilyoster. And if you want to support the show, become a subscriber to the ParentData Newsletter at parentdata.org, where I write weekly posts on everything to do with parents and data to help you make better, more informed parenting decisions.

There are a lot of ways you can help people find out about us. Leave a rating or a review on Apple Podcasts. Text your friend about something you learned from this episode. Debate your mother-in-law about the merits of something parents do now that is totally different from what she did. Post a story to your Instagram debunking a panic headline of your own. Just remember to mention the podcast too. Right, Penelope?

This transcript was automatically generated and may contain small errors.

Community Guidelines

Log in