For most of the first year of my daughter’s life, we lived in Lisbon, Portugal. My husband was doing research for his doctorate in history, and I was working on my master’s thesis (I had recently completed all of the coursework for a master’s in child development and half of my master’s in social work, with an emphasis on clinical work with children and families). The subject of that thesis was first-time parents of toddlers. My mind that sunny Portuguese fall and winter was a mix of highbrow and lowbrow parenting ideas: the notion of Winnicott’s “good enough mother” and Margaret Mahler’s concepts of separation and individuation in infant development, interspersed with baby puree recipes and a blog on infant sleep that taught me how to settle my daughter into a nap routine.

Our apartment was bigger and brighter than the place we’d left behind in New York, and the farmer’s market up the street stocked beautiful produce all year long, unlike the sea of onions we found in Fort Greene Park in January. Our lives in Portugal were lovely, but we were alone: our family and friends were an ocean away. In this way, I think my experience of early motherhood was a version of what many of us face: we bring babies into communities into which we may not have deep ties. Often, we are far from family.

My older sister and my 11-year-old niece came to visit Lisbon when my daughter was 8 months old and learning to army crawl and scoot on her bum. One day, she inched her way closer and closer to the freestanding radiator that heated our living room. I had eyed this development with a mixture of worry and resignation: she was a baby, so I figured I would just move her away, and that my days of being able to switch the laundry out or go to the bathroom alone while she was awake were numbered. But as she inched closer to the radiator, my sister scooped her up.

“No,” she said firmly to baby Lola, in a voice that was authoritative but not unkind. “No.” She put Lola back on the floor but further from the radiator and facing the opposite direction. And every time Lola again made her way towards the hot appliance, Caitlin lifted her up and offered Lola this firm but friendly no. In the days that followed, I repeated this tactic. Lola never touched the radiator, and eventually, she stopped moving towards it. I put dangerous items out of reach, but that “no” served us both through baby- and toddlerhood. And the notion of her responsiveness — the idea that I had not given her quite enough credit for taking in a limit and incorporating it into her independent exploration and play — bloomed.

I often wonder what would have happened if I had been even more isolated during my daughter’s early years: what if my sister had not spent her February break with us? Would I have figured out that my daughter’s grasp of limits and language was already there, even before she could walk or talk? And what else did I miss out on, being so far from her and my other big sister? I was on my way to becoming an “expert” in parenting, but I was a novice who was far from my parents and my in-laws, who raised eight children between them.

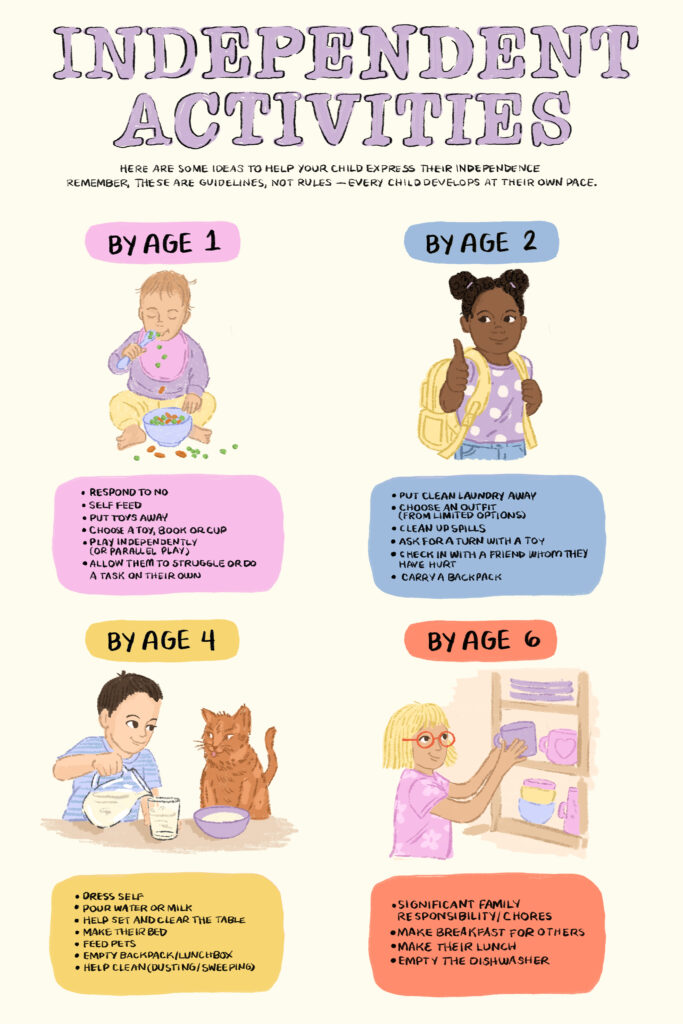

So many of us parent in a vacuum: we have little to do with children until our friends start having them or until we have our own. This makes it hard to know what our children are capable of. Once they arrive, we tend to both over- and underestimate them: we wonder why our 2-year-old can’t accept that it’s time to leave the park, but we don’t allow our 4-year-old to pour their own milk. Limits and independence are deeply interconnected (a child who knows to pause at a street corner is building the skills that will, in a few years, allow them to cross safely on their own). My daughter’s grasp of “no” allowed me to leave her playing while I put away clean laundry or read the news. It gave her some freedom in a space: she knew what was hers to explore, and what was not. Was there some risk in relying on her understanding of this limit? Maybe. But avoiding risk has its own dangers, too.

My sister was then the parent of an 11-year-old. She knew that raising a child involves holding two unwieldy tasks in your arms simultaneously: you must care for the little person in front of you, and you must also parent for the future, for the child or young adult you hope will stand in front of you in two, five, or 15 years. This means setting limits and fostering independence.

Why it’s important to help kids become more independent

Why does it matter if our kids become independent? Well, in the long term, we need them to pour their own milk and put on their shoes. But in the short term, doing so gives them a sense of agency and efficacy. There’s good reason to believe that kids are less independent than they were a few decades ago, and some reason to believe that this may be a contributing factor in anxiety.

Perhaps some of our growing (and important!) interest in data has held us back here. There’s very little quantitative data about what children are capable of at different ages. In part, this is because such expectations for autonomy and independence are regionally and culturally specific, for obvious reasons, and different children vary quite a bit in their readiness for different tasks. (For one thing, both judgment and fine- and gross-motor skills can evolve at dramatically different rates even among culturally similar children.) But we do have a lot of observational information, largely from teachers and professional caregivers, about what most children are capable of at different ages.

And we can do our own data collection. We can observe what our children are capable of as they play (the child who is pouring water in the bath can begin to learn to pour their own milk into their cereal). We can observe or ask what our kids are capable of in their classrooms in order to get a sense of what tasks they could be mastering at home. (Of course, kids may initially resist completing familiar school tasks at home, particularly when they are tired.) And while comparison sometimes gets a bad rap, in reality, there’s a lot of value in looking at kids a bit older than yours and asking yourself: could my kid do that? What skills would they need to be able to get there?

Parenthood, as ever, is a dizzying juggling of cliches: you live in the here and now, and you play the long game. If we want to raise children who can set out bravely into a complex world, we must sometimes push them forward — allow them to test their limits and make mistakes.

How to help children become more independent

The gulf between crawling away from the living room radiator and riding around the neighborhood on a bike (as my daughter eventually did) feels vast. But any large task can be broken down into small ones that can be taught over weeks, months, and years.

Identifying developmentally appropriate tasks can be done by observation, but it’s fair, too, to think about what would reduce your stress and domestic workload: could my kid put away their clean laundry? Could they learn to turn on the TV on Saturday mornings and navigate their way to Bluey? Could they be the one to serve the gross-smelling food to the perpetually hungry cat?

Scaffold the task for your child

There are many ways to scaffold kids’ mastery of new tasks. One educational strategy is to first do it for them, then do it with them, then watch them do it, until finally they can do it independently. If we stick to the example of the cereal, we might say to a 4-year-old: “I think you’re getting to be big enough that you could get your own cereal ready in the morning!” (I’d suggest using a tone that communicates that this is an exciting sign of maturity, not the first step on a road paved with endless household tasks that the adults can’t wait to offload onto the rising generation.) You would then ask them to pay attention as you narrate choosing a bowl, filling it with cereal, and then fetching the milk from the refrigerator, pouring it carefully into the bowl, and returning it to the fridge (this last point remains challenging even for some adults in my household). The next day, you might pour the cereal and the milk together. The following day, you might stand nearby (paper towels at the ready) and watch your child fill the bowl. And eventually, they can take this task over completely, leaving you free to dry your hair (or sleep in!).

Let them complete the final step

Another strategy for fostering independence is known as “backward chaining.” In this approach, you would similarly break the task down into steps, narrate your actions, and ask your kid to observe you, but you’d allow them to complete the final step under your supervision, giving them a sense of both accomplishment and possibility — this is a task that I can learn to do! Because the child is immediately successful — they are asked to pour the milk into the bowl of cereal that you have prepared — they can say, “I helped get my breakfast ready!” Frustration is more limited, and motivation is higher. Earlier steps are introduced on subsequent days.

Adjust your home environment

It can be helpful to consider the ways in which your home environment might be getting in the way of your child’s independence: a mudroom without hooks at a child’s level will prevent even a motivated kid from hanging up their coat at the end of the day, and a coat that lacks a fabric loop cannot easily be hung. These are simple fixes and so is finding a low kitchen drawer in which you can store bowls and cups that your child can easily reach, moving the shampoo onto the side of the bath so that your 5-year-old can easily reach it and learn to wash their hair, or simply deciding that you will no longer carry your child’s backpack on the walk into school. Make use of sturdy stools and of your child’s ever-growing capacity to do hard things.

Get comfortable with mistakes

Fostering independence requires something else from us, however, and this piece is challenging for me, personally, and for many parents that I know. We must tolerate mistakes, mess, and chaos in a world that already feels depressingly chaotic and error-ridden. We must also learn to accept work that is not completed to our standards. We do not have to learn to enjoy these things, but if an enormous volume of milk spills onto the counter and trickles onto the floor, we must calmly offer our child the paper towels in a way that communicates that mistakes are an inevitable and non-catastrophic part of the process. If your first grader, tasked with making their lunch, decides to eat cream cheese and jam sandwiches every day for six weeks straight, I recommend keeping your objections to yourself.

Consider what boundaries are essential to your sanity: I don’t allow my kids to eat anywhere other than the table, which allows me to be relatively zen about kitchen spills and chaotic dresser drawers. And we must remind ourselves that mishaps are part of the goal: the child who bikes alone around the neighborhood may fall off their bicycle, scraping their knee. They may get lost. They may be chased by a mean little dog. That’s okay. Because they’ll come home — shaken, possibly, or maybe just triumphant — secure in the knowledge that, faced with a pickle, they figured out what to do.

Finally, we can prevent ourselves from stepping in by reframing these everyday tasks as learning opportunities. Which, of course, they are. Because raising children who can independently cross the street, cut up their own chicken, and make difficult decisions in stressful situations is, in fact, the end goal. Perhaps, if we are lucky, they will hear our voices in their head as they try to figure out what to do.

Community Guidelines

Log in

Genuine question – how do you get younger kids to actually do this stuff? I have twins who are almost 4, and one of them will dress and undress himself, put his shoes on, help with basic things – but the other just absolutely refuses to do any of that and we know he’s capable of it. He’s challenging behaviorally in other ways – anybody have tips for pushing independence with a kid who doesn’t want independence?

I have the same question! The novelty wears off really quickly for my almost 4-year-old. The issue isn’t so much scaffolding or teaching her, but getting her to (want to) do it.

Hi there! It’s challenging to respond without more background info but two things that can help are firm but friendly (even playful!) limits around first/then (first you get dressed, and then you can have breakfast), or your classic sticker chart to help motivate forming a particular (and specific) habit. It’s also true that some kids experience a push towards independence as a lack of care and they may dig into helplessness. If that’s the case, you can combine a push in one area with some babying in another, if that makes sense.

Hi Jen, see the response below! Not sure that will be helpful, but… Thanks for reading!

I agree with this generally and in many specifics. At 4 my kids weren’t strong enough to lift and manipulate a full milk carton. Probably by about age 6 or so they could handle their own breakfast. And I do find I need to supervise what my kids eat to some extent. They don’t always pick a reasonable diet left to their own devices, and unlike Frances they seem like they don’t get tired of bread and jam. But I totally agree with the overall point that they need to be allowed to do things for themselves, and that they have to be able to make low-stakes mistakes. Letting them set their own bedtimes (within guardrails) starting about age 9 is one of the ways we’ve done this.

This article is wonderful. As a former elementary educator I understand how important independence is, and this article will help me implement strategies to teach my own kids to be more independent! Sharing with my kids’ prek too!

Love love loved this article! I read your content to guide me through what we are going through in the now, but I really want to prepare my son for the real world, and loved this take on what we can do now to prep for future. I’d love to see more like this… in particular, I am interested in teaching emotional resilience but not sure where to start, thank you!