On Instagram recently I was asked, “Our baby was born by C-section, and my husband says that we should have him eat my poop to stay healthy. Is this right?” The answer to this question, you will not be surprised to learn, is that it is not a good idea to feed your baby your poop. However, the idea doesn’t come out of nowhere, and it relates to a term you might have heard: vaginal seeding.

During a vaginal birth, when an infant goes through the birth canal, they pick up bacteria from mom — the bacteria that colonize the mother’s microbiome. With a C-section, this transfer doesn’t happen. That could mean that the mode of birth affects the infant microbiome and has led people to raise concerns that something microbial might be “missed” during a cesarean birth.

This in turn has led to the question of whether it might be possible to replace some of those missed microbes, through vaginal seeding. A recent JAMA Pediatrics viewpoint argued that vaginal seeding could be key to improving infant health. On the other hand, official bodies like the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists do not recommend this.

What does the data say? As we’ll see below, the direct data is very limited, but we’ll be able to piece together indirect data to make some progress on an answer.

First, what is the microbiome?

The microbiome is the community of roughly 100 trillion microbes that live in and on you, mostly in your gut. These include bacteria, fungi, and viruses. They are important for your health, including digestion and immunity. Your microbiome is impacted by your environment, what you eat, your genetics, medications, and a host of other things.

What is vaginal seeding and why do some people do it?

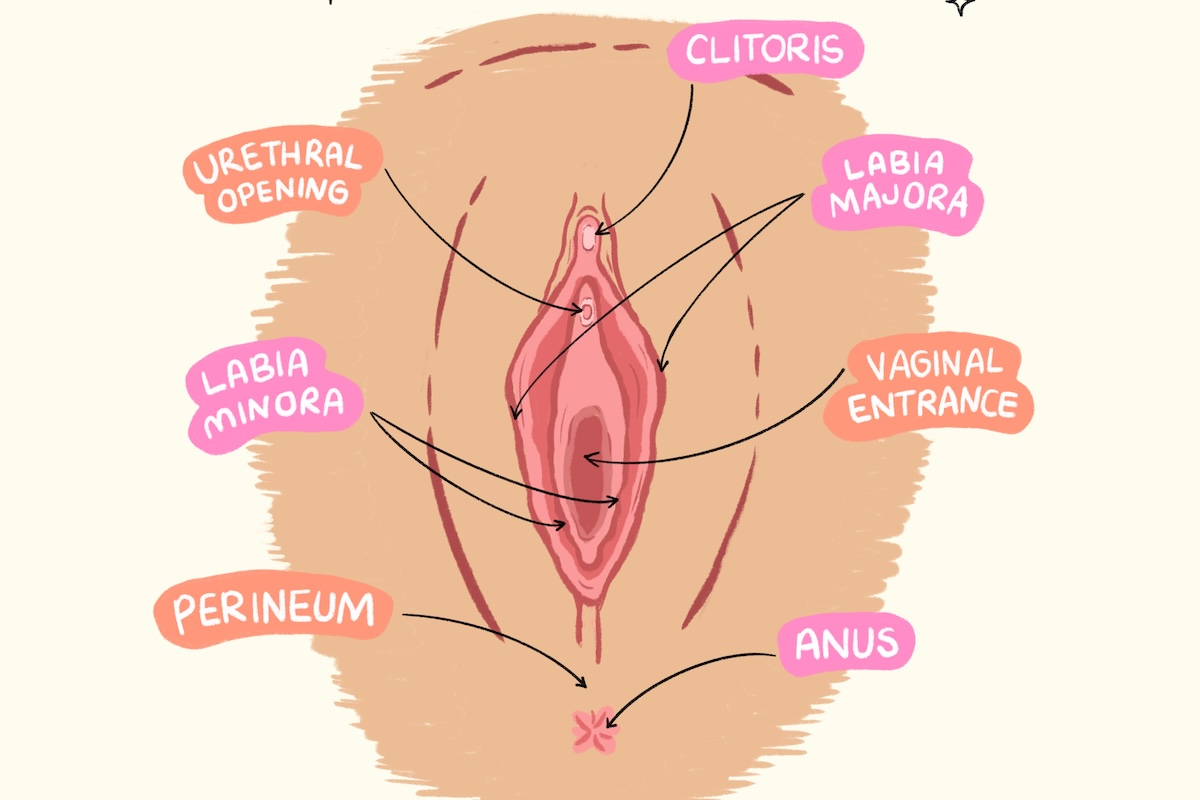

Vaginal seeding is the practice of wiping the birth mother’s vaginal fluids on a newborn infant’s mouth, face, and skin after a C-section with the goal of helping the baby establish their own microbiome. (Importantly, it has nothing to do with eating poop, as the person on Instagram asked.)

The idea is to introduce some of the microbes that would have been acquired from the birth mother during vaginal delivery to a baby born by C-section. It has been noted in the data that infants born via C-section are at higher risk for several conditions (example: asthma). There is speculation that this could be a result of more limited exposure to the maternal microbiome through vaginal birth, which has led to the idea that we should “seed” infants with the maternal microbiome through wiping them.

What does the data say about the impacts of vaginal seeding?

The direct evidence on the impacts of vaginal seeding on infants is limited. This is a question that lends itself well to a randomized trial, and some are underway, but studies so far have been small, and their results are conflicting.

A study of 76 women published in 2023 showed small differences in neurodevelopmental scores at the age of six months for infants randomized to vaginal seeding rather than a control condition. It also found differences in the gut microbiome at this age; the study did not follow infants for longer. In contrast, a 2023 study with 120 women followed participants through 24 months and found no differences in allergies or weight at any time points. Neither study showed any adverse effects.

Again, more studies are underway, and we are likely to learn much more over time. But that’s not helpful for people who are having a baby now. So it makes sense to look a bit more at the theory — and the data behind why we might suspect this would be true.

What is the theory behind vaginal seeding?

The theory behind vaginal seeding impacting infants and children relies on three links: the link between delivery mode and microbiome, the link between vaginal seeding and microbiome, and the links between C-section and health. There are data on each.

Does the mode of delivery affect the microbiome?

Delivery mode (C-section vs. vaginal) does affect the microbiome. A systematic review from 2016 summarizes this evidence, showing significant differences in infant microbiome based on delivery mode. These differences are in which bacteria are the most prevalent and how many types there are. This isn’t a case in which there are some types that are obviously good or obviously bad, so the focus is just on whether there are differences.

There are differences, but they fade after six months. At this point, the microbiome still differs across people but is not closely linked to delivery mode.

Does vaginal seeding work for changing the microbiome?

The evidence here depends on the time frame. In the short period after birth — one day and one month — there is evidence of impacts on the microbiome. It’s less clear that this persists; one of the studies cited above on efficacy, for example, also studied whether the microbiome was affected and found small and non-significant differences at six months. This isn’t very surprising given that the microbiome changes in response to what we consume and other exposures.

Typically, vaginal seeding works by the swabbing approach, but other versions have been tried. For example, in this small study, researchers created a treatment based on the birth mother’s fecal microbiota, which was given by mouth to infants. This procedure is, actually, pretty close to having the baby eat a sample of mom’s poop, albeit one that has been diluted and processed carefully. It’s not something you could (or should) replicate at home. The treatment caused a change in the microbiome to more closely resemble babies born vaginally, at least through three months.

Is there a link between cesarean section and overall health?

The weakest part of this theory is the link between C-section delivery and health. The particular health impacts that are often cited are allergies (and related issues like asthma) and obesity. The theory is that these are impacted by the microbiome, and therefore if the microbiome is affected, that might drive health differences.

It is true that there are some small correlations between C-section delivery and these outcomes (here’s an example of a systematic review). However, these results are generally drawn from observational studies, and they are therefore subject to significant bias. The group that gets C-sections is not usually random, and they differ in ways that might impact the outcomes.

For example, this study compares children by birth method on obesity, diabetes, and several other health outcomes. It does find some small differences, but if you look at the demographics of the pregnant women in the two groups, they are significantly different in many ways. That includes age, BMI, smoking, and diabetes. The infants also differ in gestational age and birth weight. With all of this, it’s simply very hard to conclude that health differences are due to birth mode instead of something else.

This problem plagues the entire literature. Moreover, even the studies that do find effects (like this one, on food allergy) tend to find only small impacts, or only on some outcomes or in some subgroups. The small and inconsistent estimates make it especially plausible that any effects we see are driven by bias and not a true impact.

Closing thoughts

The underlying idea that the microbiome is affected by delivery mode, at least short-term, seems correct. Further, the idea that vaginal seeding could have some impacts also seems plausible — if, again, short-term. Where this theory holds less weight is in the possible links with health. If the link between mode of delivery and health is weak or non-existent, there is little or no problem for vaginal seeding to “fix.”

Small studies of vaginal seeding have shown no adverse effects. Until we know for sure that it is not useful, is it worth a try? ACOG (which I mentioned in the introduction) advises against it. In that opinion, the authors worry about spreading pathogens with a DIY approach to this seeding and see no evidence of benefits. I believe the data supports this position.

The bottom line

- Vaginal seeding is the practice of wiping the birth mother’s vaginal fluids on a newborn infant’s mouth, face, and skin after a C-section with the goal of helping the baby establish their own microbiome.

- The direct evidence on the impacts of vaginal seeding on infants is limited, but the theory of why it might be worth doing relies on three links: the link between delivery mode and microbiome, the link between vaginal seeding and microbiome, and the links between C-section and health.

- There are a lot of unknowns right now, but the idea that the microbiome is affected by delivery mode and that vaginal seeding could have some impacts is plausible at least in the short term. However, the possible links between vaginal seeding and overall health are less plausible.

- Small studies of vaginal seeding have shown no adverse effects, but there are also no clear benefits based on the data we have now.

Log in

Is there any evidence of the impact of breastfeeding on microbiome development? I’m a 2x c-section mom—both kids were breech—and have been wondering what else might be more plausible in terms of promoting healthy microbiome development (beyond a healthy / diverse diet when they start eating real foods).