I don’t look at as many vulvas as the typical OB-GYN does. I don’t look at as many as I used to when I was doing my internal medicine residency in an underserved area of the Bronx, where I routinely performed PAP smears and screened patients for sexually transmitted infections. But in my current endocrinology practice, I talk about vulvas and vaginas more than ever.

One recent patient noted that since her periods had become less frequent, in the time in between her periods her vagina felt like the two sides of a misaligned piece of Velcro that were tugging at each other uncomfortably. She wanted to know if I thought a fancy new suite of products that included a wash and moisturizer formulated specifically for vulvar and vaginal use would help.

Another woman, in her 30s, noted that since she had her third baby, she had a dull ache in her vulva and vagina when standing, especially when she had her period. She was mystified, worried, and uncomfortable.

We think about our vulvas and vaginas a lot. They can do some pretty amazing things — bring us sexual pleasure and serve as a conduit to bring babies into the world — but they can also be uncomfortable, painful, and just plain confusing. Let’s understand a little bit more about them: how best to care for them, what can go wrong, and when we should worry.

The basics

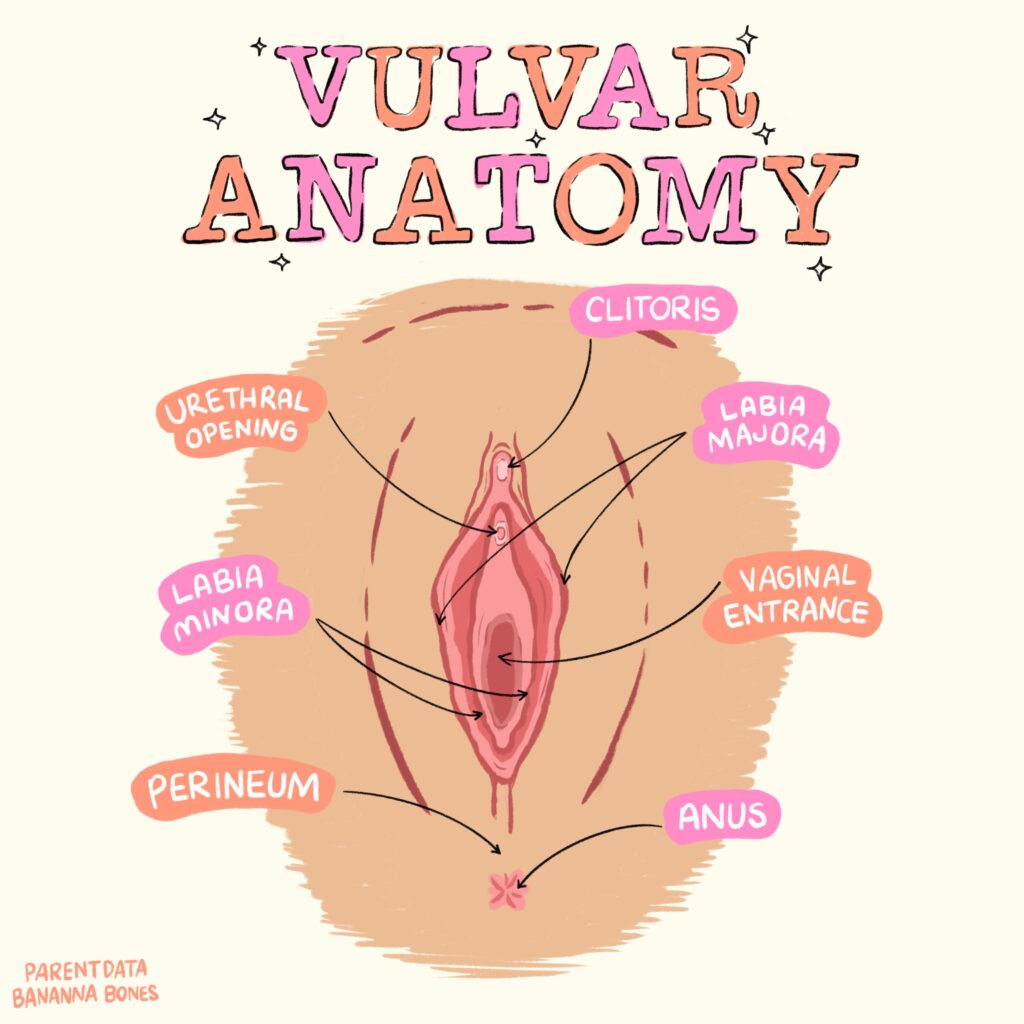

The vulva is the female external genitalia. It includes the labia majora and labia minora — the inner and outer lips — the clitoris, and the vulvar vestibule, into which the urethra and vagina open.

The vagina extends from the vulva to the cervix, the doughnut-shaped entrance to the uterus. When the vagina is empty, it is like a flattened tube with its walls touching one another. But under the right circumstances it can accommodate an eight-pound baby — a fact that never ceases to amaze me despite having given birth to four babies.

Vaginas come in all lengths and widths. The surface area of the vaginal walls in adult women can be as little as 34 square centimeters to as much as 164 square centimeters.

The skin of the vulva and the mucous membrane lining the vagina, called the mucosa, is delicate. Beneath the vaginal mucosa are layers of muscle and two types of glands: Bartholin glands and Skene glands. These both contribute to the production of vaginal lubrication and discharge. There are also many small blood vessels that support the muscle and mucosa and contribute to vaginal lubrication.

Vulvas and vaginas during puberty

Prior to puberty, not much is going on in the vulvas and vaginas of girls. A thin tissue called the hymen stretches across the entrance to the vagina, but it typically contains holes, or perforations, and is delicate enough that a fall on the playground could rupture it. Usually by the time of a girl’s first period, the hymen is nearly gone.

During puberty, the ovaries are stimulated by the pituitary gland to start making estrogen. In response to rising estrogen levels, the vagina starts to produce a thin, neutral-smelling discharge called leukorrhea. This typically begins 6 to 12 months before a girl’s first menstrual period.

Vulvas and vaginas in the reproductive years

Once regular menstrual cycles are established — this can take up to a year after a girl’s first period — women and girls typically note predictable changes in vaginal discharge. Over the course of a normal menstrual cycle, estrogen levels rise and fall. When estrogen levels are high just before ovulation, women often note more, thicker vaginal discharge than at other times in the menstrual cycle.

Vaginas and vulvas have many normal odors. Some women will notice that their typical vaginal odor will change or wax and wane in pungency over the course of their menstrual cycle. Sexual contact can also cause a change in vaginal odor — a shift my human-sexuality professor in college called “eau de rotting sperm.”

Vulvas and vaginas during pregnancy

Blood vessels are more dilated throughout the body during pregnancy, and blood volume increases by about 40%. Add to this fact that estrogen levels are orders of magnitude higher than in non-pregnant women, and you have a setup for significantly increased vaginal discharge.

Because pelvic blood flow is increased, some women will also experience swelling of the vulva and vaginal walls. The pressure of the walls of pelvic veins, which are thinner than the walls of arteries, including those in the vulva and vagina, can lead to varicose veins in that area.

Of course, the most amazing thing vulvas and vaginas do during pregnancy is expand to allow the passage of a baby and then relatively quickly return to their pre-pregnancy condition. During pregnancy the muscles and ligaments that line the vagina relax and the folds in the vaginal wall flatten out. Immediately after giving birth, the vaginal opening into the vulva is somewhat larger. But within 6 to 12 weeks, the vaginal opening in the vulva and the vagina itself revert to their original dimensions.

Vulvas and vaginas during the perimenopausal transition

As we’ve noted, estrogen has a significant effect on vaginal discharge and lubrication. During the perimenopausal transition, estrogen levels can, at times, be very high, and at other times levels are very low. As perimenopause progresses, estrogen levels trend lower and lower.

Low estrogen levels result in decreased vaginal lubrication and vaginal dryness. Vaginal dryness can be uncomfortable and can lead to a shift in the bacteria living in the vagina and vulva. Without estrogen, the skin of the vulva and mucosa of the vagina thins and loses elasticity. The muscles that line the vagina can also weaken.

These changes allow the vagina to sag down and pull the opening of the urethra closer to the vagina and the anus. The change in bacteria and the proximity of the urethra to the vagina and anus can lead to more yeast infections and urinary tract infections.

How should you care for your vulva and vagina?

You have probably been caring for your vulva and vagina for decades, but if you, like me, live with a pubescent girl — or will someday — it is important to review some basics. Vulvas just need gentle washing with water and maybe a little gentle soap. No fancy products are needed; they are more likely to cause irritation than to be helpful. Vaginas are self-cleaning. They don’t need your help staying clean — ever. If you are experiencing vaginal dryness, over-the-counter vaginal moisturizers like Replens can be helpful.

If something wasn’t made to go in a vagina, it doesn’t belong there. The list of things that belong in a vagina is pretty short. Penises and fingers (with permission only). Contraceptives like condoms and diaphragms, and sex toys and lube designed for vaginas, are okay. Tampons and menstrual cups, yes. Medicines like Monistat or vaginal estrogen are okay, as are vaginal ultrasound probes, wands used in pelvic floor therapy, and specula (only when operated by skilled medical professionals).

Pretty much nothing else belongs in your vagina, including jade eggs, douches, or garlic — purported to treat yeast infections. While healthy vaginal bacteria are critical to preventing infections, especially yeast infections, the best data supporting the use of probiotics is specific to lactobacilli taken orally.

What symptoms should I worry about?

Like many of our body systems, our vulvas and vaginas can develop issues from time to time. Some are common, like yeast infections, while others are more rare, but it can be helpful to know when a symptom warrants your doctor’s attention.

Itching

Vulvar and vaginal itching is quite common. One-third to one-half of all vaginal complaints are due to vulvar dermatitis — irritation of the delicate skin of the vulva.

Vulvar dermatitis is often caused by soaps or lotions, detergents used to launder underwear, and panty liners. If you can identify the possible irritant and eliminate it and the symptoms resolve, that is great news.

If you cannot identify an irritant or the itching persists despite making changes, it is time to place a call to your doctor. Other causes of itching include infections such as a yeast infection or bacterial vaginosis and other conditions such as lichen sclerosus, which may require specific tests to diagnose and treatment with prescription medications.

Discharge

As we discussed above, vaginal discharge can be completely normal and is important for keeping the tissues of the vulva and vagina healthy. Normal vaginal discharge does not have an odor.

Abnormal vaginal discharge may be foul- or fishy-smelling, and it may be foamy, yellow-green, or thick like curdled milk. Abnormal discharge may also be associated with vulvar itching or vulvar, vaginal, or pelvic pain.

The most common cause of abnormal vaginal discharge is infection. Most infections should be treated with antibiotics or antifungal medications applied to the vagina or taken orally. It is important to talk to your doctor if you are having abnormal vaginal discharge so the cause can be promptly diagnosed and treated.

Pain

Vulvar and vaginal pain are never normal and should be addressed with your doctor promptly. It is helpful for your doctor if you can pay attention to some details about the pain you are experiencing.

What is the quality of the pain — sharp, burning, or aching? Is it present all the time or does it come and go? If it comes and goes, do certain activities like standing, running, or having sex make the pain worse? Is the pain worse around your period? Can you point with one finger to where the pain is or where it is worst? Do you have other symptoms with the pain such as vaginal discharge or vulvar itching?

There are many causes of vulvar and vaginal pain. Certainly infections can cause pain.

Blockage of the Bartholin glands can cause buildup of fluid, called a Bartholin cyst. That fluid can then become infected, called a Bartholin abscess. Both can be painful, and they account for about 2% of gynecology visits.

Aching pain, especially when it is worse with standing, running, or around your period, can be related to vulvar and vaginal varicosities, which can be present in about 4% of women. The presence of pain from varicosities outside of pregnancy is called pelvic congestion syndrome. Pelvic congestion syndrome primarily affects women who have had multiple pregnancies, and it typically improves with menopause.

Many women will experience similar symptoms with uterine prolapse, a condition in which the uterus slumps down into the vagina due to weakness in the muscles of the pelvic floor and other supporting structures. Between 3% and 6% of women will experience uterine prolapse, and having given birth vaginally is a risk factor. It can often be managed with pelvic floor therapy, but a subset of women will need surgical intervention to adequately manage their symptoms.

The bottom line

- Vulvas and vaginas change as our bodies progress from puberty through the childbearing years and into menopause. One of the most obvious changes is in vaginal discharge.

- Vulvas and vaginas require very little special care beyond simple washing of the vulva — vaginas are self-cleaning — and routine examination from your doctor.

- With menopause, many women experience vaginal dryness. Beyond causing discomfort, vaginal dryness can lead to anatomic changes that predispose women to infection. This can often be effectively treated with vaginal estrogen.

- Vulvar and vaginal itching and pain and abnormal discharge should be addressed with your doctor promptly.

Log in

Thanks for the lichen sclerosus shout out! Never feels like it gets discussed enough, and appreciate it – feel seen!