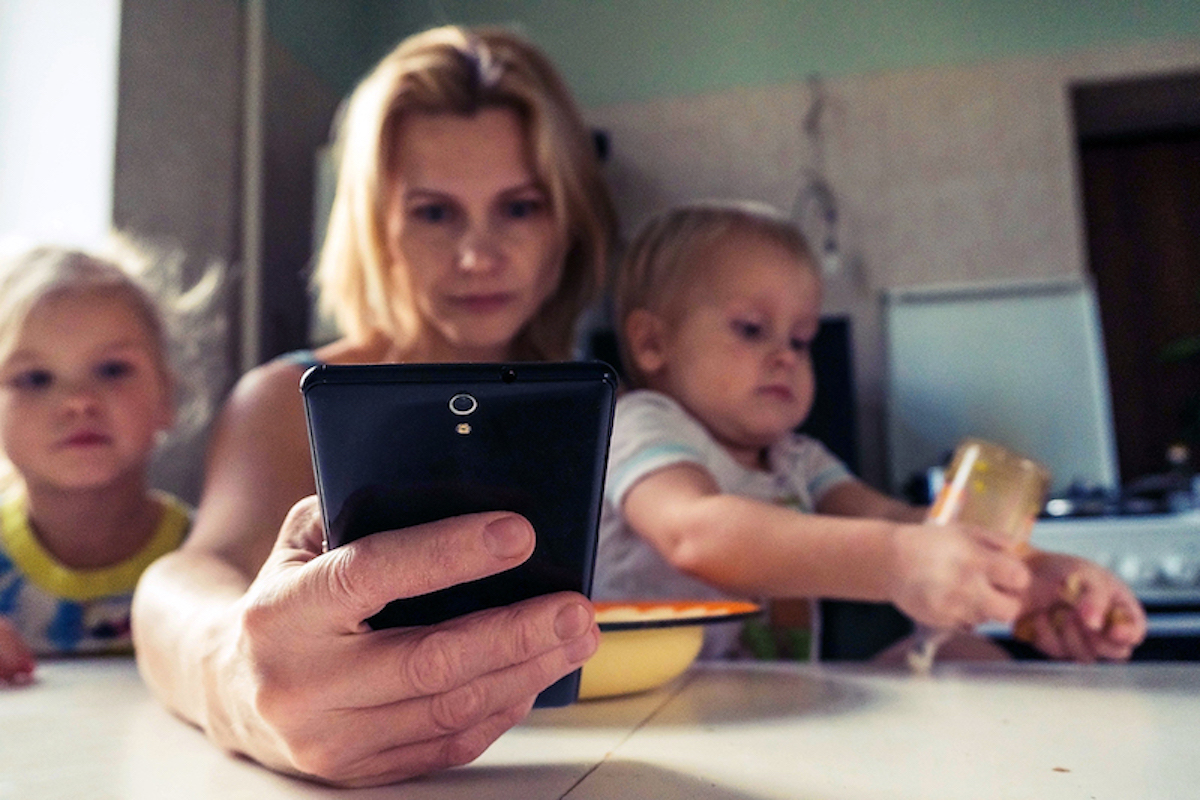

If you’re a parent who reads the news, over the summer you probably heard a lot about screens. And even now, as kids go back to school, we’re hearing plenty about phones. No phones in schools. Put your phone in a Yondr pouch. Hide your phone in your backpack. Students are doing TikToks in the bathroom. Take their phones away.

At the forefront of many of these conversations is Jonathan Haidt. His book The Anxious Generation has galvanized a number of these conversations, and although there are other people who have contributed to the discussion, Jon is really in the vanguard of talking about changes that he thinks we need to make around kids and their mental health and phones and schools.

On today’s episode, I’m speaking with him. Much of what Jon says makes sense to a lot of people, but he’s also gotten a fair amount of pushback, particularly on the question of whether phones are truly the boogeyman for teen mental health. In this conversation, Jon and I get into that. There are many things on which we agree and some where we don’t necessarily agree. And I think having conversations like this — with people who respect each other but don’t agree on everything — is part of how we figure out these hard and thorny questions in parenting and in general.

Here are three highlights from the conversation:

What does a “phone-based childhood” mean, and how does it impact kids’ mental health?

So my argument in the book is that it was the gradual loss of the play-based childhood, which was really from the ’80s and especially the ’90s. You’re taking away this thing that kids need to be stronger.

They don’t get depressed yet. They’re actually hanging out on the internet. And the early internet wasn’t so bad. But it’s between 2010 and 2015 that everything changes, when they go from flip phones to smartphones with front-facing cameras, unlimited data plans, and now you can be on your phone literally all day long, and some kids are. So 2010 to 2015, everything changes, the play-based childhood is gone. And now most kids have a phone-based childhood.

As parents, is it our responsibility to accept that it is better for our children to have phone-free schools?

But I think other than the kids themselves, the biggest pushback here is from parents. “What if my kid needs me?” And I almost feel like it’s a responsibility as parents to accept that this is better for our children.

And so a lot of parents have gotten in the habit of that since 2010 or even before, since they had flip phones. But that’s a problem. It’s not an audience we need to cater to. It’s actually a problem. And the kids already have so much trouble focusing. They always do. And they don’t have developed prefrontal cortices. They don’t have full executive control. So if they’re in class, they need to be focusing on the teacher. And okay, if they’re flirting with the person next to them, that’s okay because that’s social skills. They don’t need to be texting with their mother or other kids or strangers in other countries. So yeah, I think those parents just have to get over it. Again, I understand the concern. I have two kids in New York City public schools, but this is where we have to overcome our anxieties. And it’s the same for letting them out to play.

Should you treat social media more like drugs or like driving?

And then it breaks our heart and we say yes, and that puts pressure on everyone else. And so before you know it, the vast majority of kids in middle school have it. And so it’s not up to individual families, in a sense. Yes, if you’re a very strong parent, you want to set boundaries, you can do it, but it’s going to be a struggle. But if you can do it with the parents of your kids’ three or four best friends, and you say, “Sweetheart, I know you’re going into sixth grade next year, and some of the kids already have iPhones in fifth grade. But you know what? Me and the parents of Billy and Tommy and whoever, we’ve all decided you’re going to get a flip phone and we want you to be able to communicate with each other. We want to be able to text with you, but you’re not getting a smartphone until high school.”

Well, then it becomes much easier. So this is not like any of those other things. Now it’s like driving in the sense that driving is very, very useful and adults need cars in this country to do their adult things. We need them. But 9-year-olds, 10-year-olds, they’d love to drive. It’d be fun, but they don’t need it. It’s not like we have to get it to them. And so for driving, we say, “How about nobody drives before 16? How about we just say that?” And I think social media needs to be the same way. Because as long as some kids are on it, there’s pressure on all of them to be on it.

Full transcript

This transcript was automatically generated and may contain small errors.

If you’re a parent who reads the news, who listens to this podcast, over the summer, you probably heard a lot about screens. And even now, as kids go back to school, we’re hearing a lot about phones. No phones in schools. Put your phone in a Yondr pouch. Hide your phone in your backpack. People are doing TikToks in the bathroom. Take their phones away.

And at the forefront of many of these conversations is Jonathan Haidt. Jonathan Haidt’s new book, The Anxious Generation, has really galvanized a lot of these conversations, and even though there are other people who’ve contributed to this, he’s really at the forefront of talking about changes that he thinks we need to make around kids and phones and schools and their mental health.

On today’s podcast, I’m talking to Jon Haidt. A lot of what Jon says makes sense to a lot of people, but he’s also gotten a fair amount of pushback, particularly around the question of whether phones are really the boogeyman for teen mental health. In this conversation, Jon and I get into that. There are a lot of things on which we agree, and there are some things where we don’t necessarily agree. And I think that having conversations like this with people who respect each other, but don’t agree on everything, is part of how we really figure out these hard and thorny questions in parenting and in general.

If you’re a listener to this podcast, you will remember that we’ve had many conversations over the past few months about these issues of screens and phones, and they’ve come from a bunch of different angles. And incorporating Jon into this conversation is really important because of how central his voice has been in talking through these issues.

This podcast is a little different than usual. We did it as a live virtual event, so you’ll hear us talk for a bit at the beginning, and then you’ll hear some listener questions. After the break, Jon Haidt.

So, I just started collecting all the studies I could find on all sides, organized them. I put them in these big Google documents, we call them collaborative review documents. And what emerges is a very interesting story where there are some studies that seem to suggest there’s no relationship. But when you dig into them, what you always find is that there is a relationship, it’s just buried. And that’s true in the correlational studies and the experimental studies. So, it began to be clear, wait, something big is going on. That was clear from my experience as a professor and probably yours. We all know our undergrads from about 2017, 2018, rates of depression were extremely high. So, what was going on with that? Anyway, that wasn’t a short answer, I’m sorry-

Anyway, that’s where I was before I started this book. Once I really dug into what the hell happened between 2010 and 2015, why is it … You graph out, chapter one has all these graphs. I have hundreds of graphs on my Google Docs. There’s really no trend in mental health data from the late ’90s to the early 2010s. It’s pretty flat. And then all of a sudden it’s like someone turned on a light switch around 2012 and girls all over the developed world begin checking into psychiatric emergency wards. So, what happened? Why did things change so quickly? So, my argument in the book is that it was the gradual loss of the play-based childhood, which was really from the ’80s and especially the ’90s across. You’re taking away this thing that kids need to be stronger.

They don’t get depressed yet. They’re actually hanging out on the internet. And the early internet wasn’t so bad. But it’s between 2010 and 2015 that everything changes when they go from flip phones, you can’t spend eight hours a day on a flip phone. They go from flip phones in 2010 to smartphones with front-facing cameras, unlimited data plans, and now you can be on your phone literally all day long, and some kids are. So, 2010 to 2015 everything changes, the phone-based childhood is gone. Sorry, the play-based childhood is gone. And now most kids have a phone-based childhood. I picked that term to sound kind of creepy. I used to like Star Trek when I was young, like, “Oh, is it carbon?” “No, captain, it’s silicon-based.” It’s a play-based to a phone-based childhood. It’s creepy.

In the ’90s it gets much safer. Drunk driving plummets, we’re locking up the sexual predators, which we didn’t do in the ’70s, so life gets really safe for kids and deaths from all sources are plummeting in the ’90s. But that’s when we freak out because we don’t trust each other anymore. And that’s when we start saying, “No, you can’t go out. But oh hey, here’s the computer. Computers are good for you, so play on a computer.”

Other people say, “Well, 2012, I mean, that was in the wake of the financial crisis.” Like no, because mental health was actually unaffected by kids at all. There’s no sign of a problem during the worst days of the financial crisis. And then basically throughout the 2010s life is getting better and better economically, but the kids are getting worse and worse. So, we can go through, and we have this in our Google Docs, we have got 15 different alternate hypotheses people have told us, and none of them can explain both the timing around 2012 and the international scope. So, you got to start thinking, when you have a global change, either it’s something about the sun, and I literally have looked into sunspots, like was there a huge increase in sunspots. Or it would be some chemical that somehow was released into the atmosphere over North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand at the same time. Unlikely. It’s not going to be the food supply, even if we use GMOs here, they didn’t use them in Europe and New Zealand.

So, if we’re just looking at the correlations, granted correlations don’t prove causation, but something huge happened to the mental health of our species practically. There is no other explanation for it. I’ve got an explanation. It fits perfectly, and I keep waiting for someone to say, “No, it was something else.” No one’s come up with anything. Do you have one? Seriously, have you heard one that you think is possible?

The other one people point to, the one that could be global is the ICD, the International Classification of Diseases. They did do a major update between ICD nine and 10 in 2015, and that would be global. Because it would affect mental health professionals in all the countries. But the numbers didn’t go up in 2015, 2016, they went up in 2012, 2013, and then they go up again around 2018 there’s another maybe an acceleration. So, we don’t see any sign in the data of a 2015 2016 change. Yeah. Okay, hit me with another one.

Section two is more compelling. It’s the longitudinal studies. If you have a population of thousands of kids that you’re tracking over time, you can look and you can see what’s their mental health over time. Then you can see, did this kid bump up her social media use at time three? Okay, yes. Well, what happened to her mental health? Oh, then her mental health got worse at time four. Conversely, if some kid’s mental health got worse at time three, and then you can see, oh, did her social media use bump up at time four? Oh, yes, that would be reverse correlation. So that’s theoretically possible. There are some studies that find it, but there are a lot more that find the forward correlation. I’m not doubting that once you’re depressed and anxious, many of the kids, especially girls, will spend more time on social media.

But there are many, many studies we have. Again, we have a whole section. There are many, many more studies that find forward core. When you do a time lag study, they find that the increases in phone use or social media use specifically I should say, they’re leading indicators of mental health problems, not the other way around. [inaudible 00:17:51], who’s one of the skeptics claims that it’s all reverse correlation. And sure, there are a couple of studies that show that, but there are many more studies that are showing forward correlation.

And then are quasi-experiments where the world randomly assigned, let’s say different towns or different cities to get high-speed internet at a different time. Or the one you referred to, I think it was by Alcott, I can’t remember. The first author was-

So, there’s correlational studies, there are time lag studies, there are lab experiments, there are quasi experiments. I’m like, “Oh, you keep saying it’s just correlational, but it’s not. What else can I do?”

You don’t need social media. So Meta is trying to control the narrative here. Meta is trying to put out the line that COSA hurts LGBTQ Kids. COSA is the Kids Online Safety Act. Meta really doesn’t want any regulation. And their main argument to the left, they speak to the right by saying, “Oh, it’s free speech violations.” To the left they say, “Don’t regulate us, because social media is a lifeline for LGBTQ and other kids from marginalized communities.” Well, guess what? To say that it’s a lifeline, the early internet was, so if you’re a gay or trans kid in a rural area in 1998, yeah, the internet was a lifeline. You could get information, you could meet people, you didn’t feel alone.

So the internet solved that problem. Now the internet evolves, and it used to be this open internet, it was all nonprofit, and the internet evolves into three or four giant companies that suck up everyone’s attention. How did they do this? By using a newsfeed that was algorithmized and engineered to keep you on it. Now, do LGBTQ kids need that? Is that what they need to find information? Hell no. Is that what they need to find community? No, there are so many other ways.

So, that’s my second point is that the purported benefits are almost all available. If we were to raise the age to 18, I argue for 16, if we raised the age of 16 for opening a social media account, no kid would suddenly be like, “How can I find information I would never think to go to Google? Or how could I find other people? I would never think to go to all sorts of other ways that people can connect.” And here’s the third, here’s the kicker, and it is that when you actually look at the evidence, when you look at young teens generally have a lot of regret. A lot of them say that it’s harmed them. A lot of them say that they wish it was … About half of them say they wish it was never invented. On all those measures of regret, LGBTQ kids are higher than non-LGBTQ.

In other words, it’s the LGBTQ kids who are especially on exploring interactions with strange men around the world who are sextorting them and humiliating them. So, it’s the LGBTQ kids who are really getting harmed by this insane open online world where you’re interacting with strangers who want sex from you. How can we be doing this to the kids? So again, sure, I’m sure some kids are benefiting, but the harms are enormous. The harms are intrinsic to social media and the benefits are not very well documented and easily available. Even if we were to raise the age to 16.

Or do you want to be in a school where as soon as there’s an emergency, everyone’s on their phone crying to their parents? That’s not going to school Security experts say that is not helpful. It is not safe for everyone to be on their phones. So phone-free schools, other than that argument, there is no pushback at all. Amazingly, not amazingly. A month ago two surveys come out, one from teachers, and it’s like over 90% say they don’t want phones in class. But here’s the big thing people don’t understand. They think, “Oh, don’t let your kids use phones in class.” But they can use them in between classes and at lunch, hell no. Because first of all, they’re missing out on socializing, on talking with their friends, on playing, on touching. There’s very little touch anymore. Kids don’t touch each other because they’re always on their phone.

So, the phone policy has to be bell to bell. I’ve been advocating for phone-free schools. At the beginning of the day, it’s useful to get to school at the beginning of day. You put it in a Yondr pouch, you put it in a phone lock or you put it in a basket-

When I talked to the Yondr people about this, I said, “Look, this is what’s happening. My daughter says most of the kids can get their phones out.” They said, “Well, yes, but it damages the pouch.” If the school will do inspections, then that cuts it way down. Bottom line is that schools that use Yondr seem to really like it, but they do need to enforce it. You have to do some pouch inspections, but it works. And it’s pretty straightforward. A better way I think would be phone lockers, but I don’t actually hear of many schools that are using them. So I don’t really know. But in theory, phone locker, you lock it in the morning in your home room or the front and then you get it back at the end of the day, that would be the most reliable.

What I did find evidence of is that for kids who have ADHD, this makes it a lot worse. The constant interruptions, the fragmenting of attention. Now, I should point out the way that you really learn something here would be an experiment where we randomly assign a bunch of kids to be constantly interrupted, to always to never have 30 seconds free to think, to be constantly pinged. And we do that for two or three years from say age 12 to 15. And then we test them at age 15, who’s got better concentration. Now, of course you could never do that experiment. That would be the most unethical experiment. And so in the absence of that, I can’t tell you that, oh yes, we’ve proven this. But I think teachers see it. So one actually we bring in addiction. One of the things about addiction here, we’re especially talking for the boys. So the girls, their lives are getting messed up in a dozen ways through social media. I have a whole chapter on that, chapter six.

The boys’ story is a little different, and it’s much more about video games and pornography. The boys are spending huge amounts of time on video games and pornography. They’re not as depressed as the girls. They’re actually having fun. They’re enjoying the video games, they’re enjoying the pornography. But what happens over time is the quick cheap dopamine hits, the incredible beauty of these games and the eroticism of the porn. I mean it’s beyond anything that we could have imagined when I was a kid. It conditions them to quick dopamine, which means that dopamine circuits down regulate, you need more dopamine to get to feel normal, which means that when they’re not on video games or porn, everything’s kind of just boring and uncomfortable. And it’s very hard to focus or concentrate or enjoy anything, because it’s not video games and porn. It’s not exciting. So I think my belief is that just looking at the nature of addiction, we see enough that it is affecting the way the kids are thinking.

And then it breaks our heart and we say yes, and that puts pressure on everyone else. And so before you know it, 95% of kids by the age of 11 or 12, again, I don’t don’t know the exact numbers now, but it’s around there. The vast majority of kids in middle school have it. And so, it’s not up to individual families in a sense. Yes, if you’re a very strong parent, you want to set boundaries, you can do it, but it’s going to be a struggle. But if you can do it with the parents of your kids’ three or four best friends, and you say, “Sweetheart, I know you’re going into sixth grade next year, and some of the kids already have iPhones in fifth grade. But you know what? Me and the parents of Billy and Tommy and whatever, we’ve all decided you’re going to get a flip phone and we want you to be able to communicate with each other. We want to be able to text with you, but you’re not getting a smartphone until high school.

Well, then it becomes much easier. So this is not like any of those other things. Now it’s like driving in the sense that driving is very, very useful and adults need cars in this country to do their adult things. We need them. But nine year olds, 10 year olds, they’d love to drive. It’d be fun, but they don’t need it. It’s not like we have to get it to them. And so for driving, we say, “How about nobody drives before 16? How about we just say that?” And I think social media needs to be the same way. Because as long as some kids are on it, there’s pressure on all of to be on it.

Second thing is, we do know the other parents, because we had to arrange pickups at birthday parties. So, we all know who’s Tommy’s mom and who’s … So we already are connected by text or on other devices.

And then the third thing is schools are the logical place to start this. Schools are the center of parents and teachers’ attention on a defined group of kids who know each other. And so that’s why phone-free schools is so important, so powerful. Listen, everyone in the audience, if your kid’s school allows them to keep a phone in their pocket during the day, it is probably going to reduce what your child learns. And it is going to increase the odds that your child will have anxiety and depression later, especially if they’re a girl. So if your school allows that organize with other parents, I promise you the teachers hate the phones. They want to get rid of them. The principals hate the phones. They want to get rid of them. The only reason they’re not acting is because some parents are objecting. But if you coordinate, you will get that.

And if we get our kids going six hours a day without phones, imagine if they had six hours a day to listen to a teacher and to talk with other kids. They’ve never had that before, but imagine if they did. Well, now it’s going to be a lot easier to have them do other activities in the afternoon. They won’t be as addicted if they just went six hours without it.

So if your four, five, six-year-old is watching the cartoon, if your nine-year-old is watching things on Netflix, those are stories. Those are good. You pay attention to a story for 15 minutes, 40 minutes, two hours? That’s okay. It’s the short-form videos. It’s TikTok, Instagram Reels, YouTube Shorts. Those are terrible. There’s no benefit. And my students, a lot of them are … There’s a 19-year-old undergrads. They’re hooked on it. They waste four to six hours a day a lot of them on it. There’s no benefit. They’re not stories. So don’t let your kids start on TikTok till they leave your home, I’d say.

Now, especially certainly in the elite wealthy areas where all you’ve got these intensive parents focused on their kid’s private school, those are all acting. They might have other problems in the culture there, but those are pretty quickly going phone free. Oh, move to Silicon Valley. If you move to Silicon Valley, the people who made the stuff, they know how bad it’s for kids. They don’t let the kids use it. They want your kids to use it.

Our virtual office hours event was produced by Meg Bradshaw and Kellie Lin Knott, and again, with support from our team. Keep your eye out for next month’s office hours. And remember, these virtual conversations are a perk offered for our subscribers at the plus tier. So head on over to parentdata.org to learn more about both our subscription tiers and our events.

If you have thoughts on this episode, please join the conversation on my Instagram, @profemilyoster. And if you want to support the show, become a subscriber to the ParentData newsletter at parentdata.org, where I write weekly posts on everything to do with parents and data to help you make better, more informed parenting decisions.

For example, earlier this summer, I wrote about screens and social media, particularly in schools and what the data, so far, says about how involved parents should be in monitoring it. Check it out at parentdata.org.

There are a lot of ways you can help people find out about us. Leave a rating or a review on Apple Podcasts. Text your friend about something you learned from this episode. Debate your mother-in-law about the merits of something parents do now that is totally different from what she did. Post a story to your Instagram, debunking a panic headline of your own. Just remember to mention the podcast too. Right, Penelope?

Community Guidelines

Log in

As I listened, I found myself wondering if Jon has kids, and if so how old are they/how were they interacting with cell phones during their younger years?