Respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, is a common respiratory virus. Unless you are very, very unusual, by the time you’re an adult you’ve had it many times. RSV is a seasonal virus, typically peaking in the early winter months. Nearly all children have had RSV by the time they are 2.

Perhaps because of its universality, or the fact that it is generally a mild illness in adults and older children, RSV isn’t necessarily at the forefront of our minds when we think about illness risk. However, RSV is actually a source of significant hospitalization and mortality for young babies and older adults. The first infection with RSV is generally more serious, and for little babies it can be extremely dangerous. Based on data from 2015-2016, the hospitalization rate for RSV among babies under six months was 14.7 per 1,000. That is to say: of 1,000 babies, 14.7 of them will be hospitalized for RSV, and many more will be quite sick.

I’ve written about RSV before — a summary here and a discussion of the unusual fall disease profile last year here — so I am not going to re-discuss the basic facts here. What I do want to talk about is the new RSV vaccines. There are exciting new developments in this area, focused on vaccines for older adults and for pregnant women, with the latter having the goal of protecting their infants. (Update 8/24/2023: A post on the newly FDA-approved RSV drug for infants and toddlers is here.)

I’ll start with older adults.

RSV vaccines for older adults

The burden of disease in RSV falls on young babies and older adults, who tend to have weaker immune systems. RSV causes a similar number of deaths to influenza in a typical year, and the mortality rate among patients hospitalized with RSV is estimated in the 10% range. RSV deaths among older adults well outpace deaths among young children.

In early May, the FDA approved the first RSV vaccine for adults over 60. The vaccine is made by GlaxoSmithKline and will be sold under the brand name “Arexvy.” This is a protein-based vaccine, meaning it works by introducing a protein found on the virus to the body. The protein is harmless alone, but it prompts a response that trains the immune system to recognize and combat the virus if it is introduced later.

Vaccine approval is based primarily on the large Phase 3 trial reported here. The trial recruited almost 25,000 adults over 60 and randomized half to the vaccine and half to a placebo. The primary outcome was prevention of RSV over the course of one RSV season. The vaccine was extremely good. The protection was estimated at 82% against confirmed RSV infection and 94% against severe disease. Side effects were generally mild to moderate — injection site pain and swelling, headache, joint pain.

As is common in vaccine approvals, the FDA has asked for specific follow-up on one serious thing — the need for atrial fibrillation — which was extremely rare in both groups but slightly more common in the vaccine group. With rare side effects like this, long-term monitoring after the vaccine is administered more widely is necessary and part of the overall safety profile.

The FDA is also considering a second RSV vaccine for older adults, made by Pfizer. The FDA advisory panel has recommended approval of that vaccine, but it hasn’t issued a final approval, which would be the last step. That vaccine, which will be sold under the name RENOIR, works in a similar way. The efficacy data is slightly lower (66% overall, 85% against severe disease) but also generally impressive.

Bottom line: By this fall, at least one and possibly two vaccines for RSV will be available for older adults, and I would strongly encourage anyone in this age group to get it. I’m looking at you, Dad.

RSV vaccines in pregnancy

Protecting infants from RSV is more complex.

There is an RSV vaccine for infants, marketed as Synagis, which is a monthly shot that simply delivers RSV antibodies. This vaccine is given to preterm infants under six months who are born during RSV season. Since this is the highest-risk group, it makes sense to give them the extra protection. But this approach isn’t used for full-term infants.

The alternative current approach is to generate infant protection based on vaccination among pregnant women. This is similar to what we do with the Tdap vaccine for pertussis: a vaccine during pregnancy protects an infant against pertussis until they can be vaccinated themselves. In this case, the goal is to get protection during the first months of life, when RSV infection is the most likely to lead to serious illness. An infant who is protected for six months is still very likely to get RSV as an older child, but the serious disease risk in that age range is much lower.

On May 18th, the FDA vaccine advisory council recommended approval for a vaccine for pregnant women designed to provide this protection to their fetus (note: since RSV is typically mild in adults, there is no reason to vaccinate during pregnancy for the mom’s health; this is just about the baby). The vaccine, made by Pfizer, is the same vaccine used in older adults. The final decision about approval will rest with the FDA, who will not likely make a decision for several months. But in anticipation, we can look at the data the advisory council considered.

The council considers two issues in recommending approval: efficacy and safety.

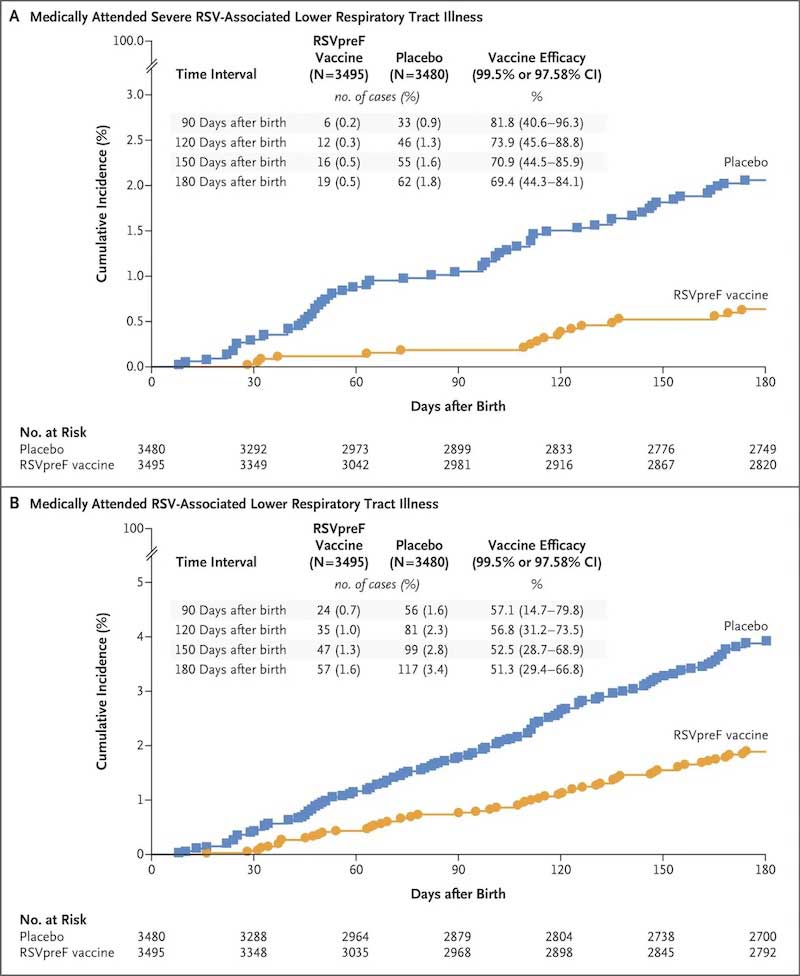

On efficacy, the council was unanimous. In a Phase 3 randomized trial with nearly 3,700 pregnant women in each arm, efficacy against severe disease in infants over the first three months of life was estimated to be 82%; there were six cases in the vaccine group, versus 33 in the placebo group. Efficacy over six months was estimated at 64%. Numbers like 6 and 33 may seem small, but if we think about aggregating up to the millions of births every year, we are talking about preventing a lot of severe disease (perhaps 30,000 cases a year).

The graphs below are their primary efficacy illustrations. The key note here, which is completely obvious in the graphs, is that the burden of disease — severe or any disease — is much higher in the placebo group.

The council was more split — a vote of 10 to 4 — on safety. The issue is a concern about elevated risk of preterm birth. In the Pfizer trial, preterm birth occurred in 5.7% of the vaccinated group and 4.7% of the placebo group (see here, slide 44). Given the sample sizes, this isn’t a significant difference, but it’s a reasonably sized number. There was also an elevation in births before 34 weeks (very preterm), from 0.3% to 0.6%. Again, this isn’t significant; we are talking about very small numbers. But some of the advisory committee members were concerned.

To give a sense of why they might be concerned, I think it’s worth looking at the numbers in detail. What we have here is a sizable impact that isn’t statistically precise. This leaves us with two possibilities. One is that it occurred by chance — that in fact, there is no difference in preterm birth; the researchers just got unlucky given the sample sizes. Another possibility is that there is a difference of about this size (or smaller or larger) but the study wasn’t large enough to detect it.

This matters, again, because of the numbers. I said above that the efficacy estimates suggest a prevention of about 30,000 cases of severe disease. A 1 percentage point increase in the preterm birth rate is about 40,000 additional preterm births; a 0.3 percentage point increase in the risk of very preterm birth is 12,000 births. If we were confident in these increases, there would be a complicated calculus to weigh these risks. We’re not confident! But the data set isn’t large enough to be confident that this isn’t true.

This reality leaves the advisers with a complicated choice — no option is completely safe. They could consider suggesting a larger data collection effort before approval, but that would delay things by at least a year (next fall rather than, possibly, this fall) and, in expectation, 30,000 severe cases. And they’d be delaying based on a signal that is statistically insignificant. In the end, the majority of the panel came down in favor of the safety profile, and the overall recommendation is for approval. It seems very likely that it will be approved, and it will then be a discussion for individual pregnant people and their doctors. The good news is that over time, post-approval, we will learn more about these risks and be able to have a better sense of tradeoffs, if there are any.

In conclusion

There is much to be excited about here. RSV has major impacts on population health, especially among the most vulnerable. For pediatricians, the idea that a huge share of RSV cases in infants could be prevented is incredibly exciting (at least based on the ones I have talked to!). And for older people, I hope the next season will see a large uptake of vaccination and a large decline in death rates.

Community Guidelines

Log in