I spend a lot of time alleviating concerns and talking parents down from all the things they’re worried about. “It’s fine” is a phrase I use … a lot. At times, though, this causes people to ask me what I do worry about with my kids. If we had to pick something to be concerned with, what should it be? For me, it’s pools.

We talk much less about water safety than we do about, say, food dyes. But water safety risks are far more important. Luckily, there are things you can do to alleviate these risks.

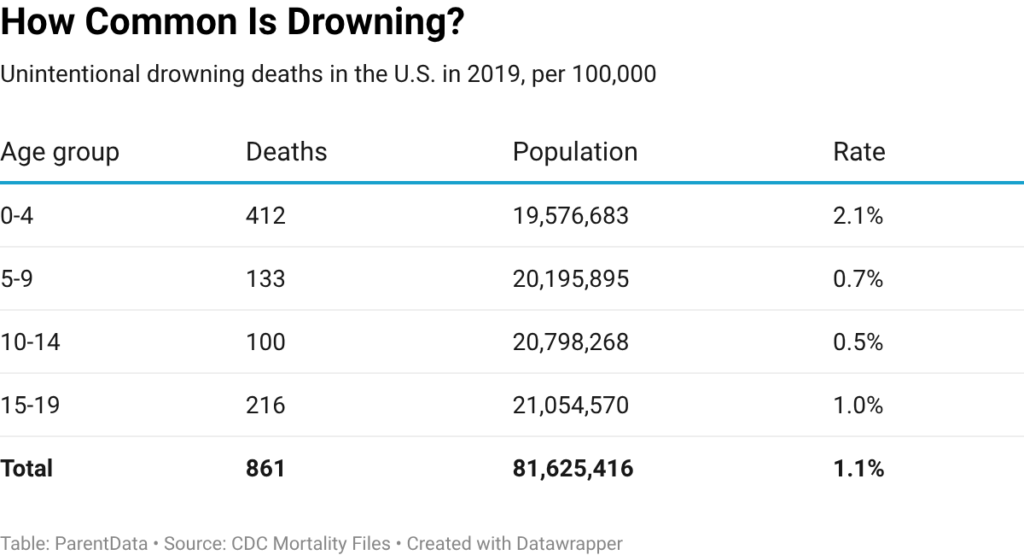

How common is drowning?

Drowning is a common cause of accidental death; the CDC reports an estimated 11 unintentional drowning deaths per day in the U.S. Children are at high risk. I used the CDC cause of death calculator to produce the table below, looking at the counts of unintentional drowning deaths in the U.S. in 2019 by age group. Among kids, the highest-risk groups are children under 4 and those 15 to 19. (This is just the U.S.; drowning is an even larger risk in much of the developing world.)

In thinking about prevention, it is helpful (if anxiety-provoking) to break down what is happening in these different age groups. In very young children (under 1), the most common drowning location is the bathtub. Infants or babies left unattended can drown, even if they are in seemingly “safe” infant tubs. In slightly older kids, the most common drowning location is pools. A toddler falls into a pool unsupervised and drowns.

This can happen incredibly fast. You’re cleaning up at the end of the day, and you take the 3-year-old’s water wings off and tell them not to go in the pool. But they walk down the steps anyway as your back is turned. And they go one step too far, and you do not turn around to find them in time. Drowning is quiet.

I am not trying to scare you. Well, maybe I am a little. I’ll talk below about swim lessons and so on, but a key thing to say, which I think the above makes clear, is that supervision of young kids around pools is just really, really important.

Drowning risks are lower for older children, partly because some of the behavior mentioned above is just less likely with a 9-year-old. If they cannot swim, they know it. With teenagers, drowning episodes more often involve open water and, in many cases, alcohol.

What lowers the risk of drowning?

Given the importance of swimming pools in drowning in younger children, it’s not surprising that much of the discussion about drowning prevention focuses on pool safety, notably pool fences and swim lessons.

Before we get into that data, there’s an important caveat about the research here. Both of these prevention approaches are difficult to study convincingly with data because drowning deaths are rare. Although they are a highly ranked cause of death among kids, the total number of deaths in this age group is very low. This makes it difficult to study with something like a randomized trial for some of the reasons I discussed in this article on statistical power. You’d need an enormous randomized trial to have any hope of seeing the impact of swim lessons on deaths. Even an observational study — say, comparing kids who have taken swim lessons with those who did not — is likely implausible just given the sample size necessary.

Instead, most of the findings on these questions come from case-control studies. In this type of study, researchers identify cases — here, pool drowning deaths — and collect information about the circumstances, for example, whether the child had swim lessons. They then identify some comparable children (similar perhaps in demographics or other characteristics) who were not drowning victims and collect the same data on them. By comparing the groups, they hope to find features that differ across the groups and then conclude something about their relative risk.

Pool fences

A review article on pool fencing concludes that it lowers drowning deaths considerably (perhaps by as much as 70%) and that four-sided fencing is better than partial fencing. The data isn’t especially high-quality, though, and the samples are small. It seems clear why fencing would matter and why full fencing would matter more, but it’s hard to show in data.

Swim lessons

The most widely cited study on swim lessons is a 2009 article that identified 88 cases of unintentional drowning and compared the cases with 273 controls. The authors looked separately at the 1-to-4 age group and the 5-to-19 age group. The differences in formal swim lessons between the cases and controls were extremely large. For the 1-to-4 age group, they calculated an 88% reduction in the risk of drowning from formal swim lessons.

However, the sample size means the estimates are extremely noisy. For the 1-to-4 age group, the data is consistent with anything from only a 3% reduction in drowning risk to a 99% reduction. For the 5-to-19 age group, the effect is about a 60% reduction in risk, but the authors cannot rule out even a 50% risk increase. Put simply, the results are suggestive, especially for the younger group, but very imprecise.

There are other problems with case-control studies — notably, the persistent worry that there are other differences between the cases and controls that are driving the effect. Formal swim lessons are likely associated with other family characteristics that could drive differences in risk. The authors try to adjust for this, but it’s challenging.

An alternative is to run a more convincing causal study on an intermediate outcome. An example of that is this trial of swim lessons, which randomized children between 2 and 3.5 years into 8 or 12 weeks of swim lessons (unfortunately, there is no no-lesson control group). The researchers find that swimming ability and water safety reactions improve in both groups and more so in the 12-week group.

From this, we conclude that, basically, you can teach kids this age to swim. Will that translate to a lower risk of drowning? It certainly seems like it could! But it is worth remembering that the circumstances in which a child is at risk of pool drowning — they are unsupervised; they fall in unexpectedly — may be quite different than even a “fall in pool simulation.” So, again, it is suggestive and encouraging but not conclusive.

You might think that there were many studies on this, but in fact, these two are the main ones. You can read a longer review here, but there aren’t significant additional studies to speak of. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends swim lessons for children 1 to 4, based largely on these two studies, and also strongly recommends them for older children for less well-stated reasons.

Does my baby need swim lessons?

The AAP does not recommend lessons for children under 1. The reason is that children this age cannot learn to swim. It’s also true that this age group is much less likely to wander off and fall into the pool. And if they did, they would be unlikely to have the presence of mind to swim to the edge.

To be clear, it’s fine to bring your baby into the pool (if you’re holding them), and they might like the water. But starting formal safety-oriented swim lessons before this age isn’t likely to be very helpful.

What about “dry drowning”?

Every year, there is a little bit of panic around the idea of “dry drowning,” which refers to a situation in which a child has (I’m summarizing) a delayed reaction to inhaling water. They seem okay, and then they are not later. This is also called “secondary drowning.”

And every year, doctors have to reassure parents not to freak out about this. Yes, kids can have a delayed reaction to water inhalation. But! First, it is very rare — only 1% to 2% of drowning cases. And second, it’s accompanied by symptoms you’d notice and worry about — persistent coughing, shortness of breath, fatigue, or vomiting. If you notice this after a risky water exposure, even a few hours after, you should react. But again, very rare.

Closing thoughts

One of the review articles on the question of swim lessons rates the evidence as a “B,” meaning it’s inconsistent and not very statistically compelling. I do not disagree, by and large, although I think there is an underlying logic to the idea that knowing how to swim could, in certain situations, matter. Also, the evidence on swim lessons shows that young kids can learn to swim. Since swimming is fun, this is one reason to do it.

Do you need to put your six-month-old in swim safety class? No. If the 3-year-old camp has swim lessons, is that a good thing? Perhaps yes.

However, I think the most important bottom line here is that swim lessons are by no means a panacea. Even if your 3-year-old’s swim instructor says your child is the next Katie Ledecky, they should not be left unsupervised with access to a pool. Even if your 9-year-old is a good swimmer, they should still not be swimming alone or at least not without someone knowing where they are.

Pools are awesome and fun, and I love them. But they are also one of the comparatively few things I do worry about.

The bottom line

- Drowning is a common cause of accidental death among children. However, the actual number of deaths is still relatively small, making prevention methods difficult to study.

- In terms of pool fencing, it seems clear why putting a fence around your pool would be important, but it’s hard to show in the data.

- The importance of swim lessons is similarly encouraging but not conclusive in the data, though starting formal safety-oriented swim lessons before the age of 1 isn’t likely to be very helpful.

- Dry drowning (or secondary drowning) is a delayed reaction to inhaling water. It is rare and accompanied by symptoms you’d notice and worry about.

- The most important thing to remember is that children should never be unsupervised near a body of water, no matter how good a swimmer they are.