There is wildfire smoke here; I have a baby and a toddler. We are trapped inside — or are we? Can we go to the playground? Is there some air quality cutoff I should be paying attention to?

—Want to breathe easier

This question recently came up with other parents while I was at the playground with my two toddlers, as we looked up at the sky, a bit hazy from wildfire smoke that was blown our way.

With short-term exposure to poor air quality and young children, the biggest concern is that small particles in the air might irritate their little lungs, causing shortness of breath or coughing, or trigger an asthma attack in a child with asthma — a condition that is very common in this age group. The challenge here is that every child has a different threshold of sensitivity, and in very young kids, a parent may not yet be aware that their child even has asthma.

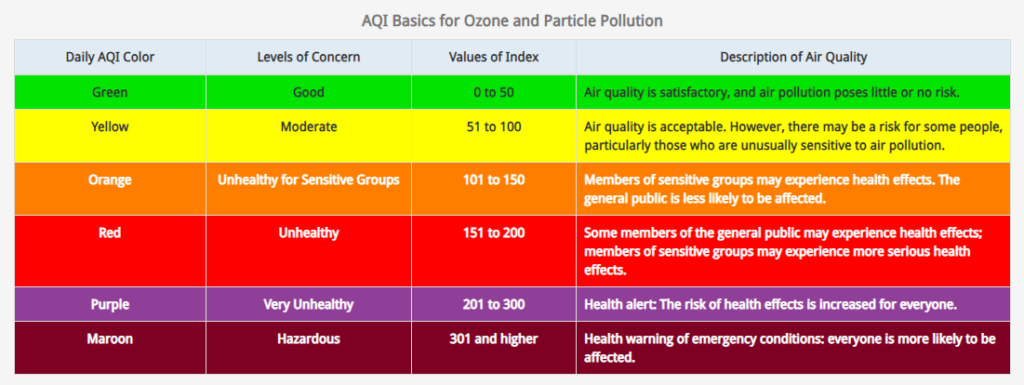

The EPA has developed color-based standards, with different colors representing different levels of risk to sensitive groups (like those with asthma or other lung disease) and the general population. The air quality index (AQI) is a number between 0 and 500, and it’s calculated by combining measurements of a number of different air pollutants, including small particles such as those from wildfire smoke. The colors are meant to indicate the level of risk when the AQI hits a certain threshold. This color-based system can be handy because it’s simple and easy to remember — green is good, red (and purple and maroon) is bad, and orange is somewhere in between.

What’s important to remember, however, is that every child is different. For a particular child, the same AQI level may or may not lead to coughing, shortness of breath, or an asthma attack. So while it’s reasonable to start with these guidelines and follow them when it’s clear-cut by staying inside if the air quality is red and above (or orange and above for a child with asthma), the most important thing to do is keep an eye on the child’s symptoms even when the air quality is below one of these AQI thresholds.

Biologically speaking, there’s nothing magical that happens at an AQI of 150 — it’s just that the EPA had to draw a line in the sand somewhere when developing these systems. So a child might be sensitive at an AQI of 140, 132, 94, or 76, and that number could even change from year to year as they grow. If a parent sees that their child is coughing or is uncharacteristically winded after playing, that’s a sign they should go home, take it easy (to the extent that toddlers are capable of this), use an inhaler if the child has asthma, and call their pediatrician for specific advice. —Chris

Community Guidelines

Log in

I understand these guidelines for short-term decisions. Does this change for areas with poorer air pollution year-round? Wildfire smoke is becoming an annual thing where we live. Long-term does this change how I should respond to outdoor activities for my kids?

i was also wondering if anyone has tips on how to handle the social pressures that comes long with restricting activity. Most parents I talk to are not even aware of what AQI means or that air pollution could be an issue. This means my daughter is sometimes excluded from play outdoors if the AQI is in the orange zone and she doesn’t understand why. It’s frustrates me that schools are not more aware, but I also realize there is a cost benefit to allowing kids to get physical activity even when air quality is poorer.