As any gym owner or diet guru knows, the peak time for dieting, at least in the U.S., is the six weeks between January 1 and February 14. People wake up on the first day of the year ready to change something, and weight often comes to mind.

That isn’t necessarily a great idea. A lot of dieting in this period is driven by external pressures — comments at the holidays, some external sense that it’s important to lose weight in the new year, some generalized diet culture.

The feeling of wanting to change something could be pointed in other directions. Weight loss may be the one you hear about, but you could also start meditating. Or embroidering. Or learning Mandarin. Or maybe, actually, you really do not need to change anything and getting through the next six weeks is enough.

I emphasize this in part because the conclusion of today’s post — spoiler alert — is that the best diet for weight loss or other health reasons (diabetes, heart disease, etc.) is going to be one you can stick with long-term. Which is only going to be possible if you find the right diet and if you’re doing it for the right reasons.

Of course, sometimes there are good reasons to try to lose weight, health-related or otherwise. As with virtually everything else, we can ask the question “What’s the best way to do this?” while acknowledging that not everyone will want to. I think of it a bit like breastfeeding. It is reasonable to talk about the best way to make breastfeeding successful, while simultaneously saying that we shouldn’t be shaming people into doing it.

Today’s post, with this background, is about grappling with the question of the “best diet,” for the data-driven dieter. I’m motivated by the timing but also by having found this excellent paper on “Optimal Diet Strategies for Weight Loss.” I’m going to start by talking about what the paper says and then give a slightly broader perspective.

What does the paper say?

It starts by noting the key underlying principle of weight loss: energy deficit. You need to burn more calories than you take in to lose weight. Period. As the paper says more formally: The key component of diets for weight loss and weight-loss maintenance is an energy deficit. Under the “calories-in, calories out” model, dietary management has focused on the concept of “eat less, move more.”

The link between weight loss, calories consumed, and exercise is a little more complex, since as you lose weight your baseline energy expenditure adjusts. But the principle of needing an energy deficit remains true. And if you want to generate this energy deficit through food, you need to eat fewer calories.

The simplest diet, then, is just … eat less. This is best epitomized by a good book I once read called The Economists’ Diet. The primary message was that to lose weight you need to weigh yourself every day and eat less. And, also, that you’ll be hungry a lot of the time. It was sort of beautiful in its simplicity, but I can see why this hasn’t caught on.

Recognizing the first point about energy deficit helps organize a discussion of diet approaches. To the extent that dieting is about weight loss (both initially and maintained), a successful diet is one in which people consistently eat fewer calories.

Particular diet options

The paper reviews many examples of two basic types of diets: those that restrict food types (low-fat, low-carb, Mediterranean, keto, etc.) and those that restrict food timing (intermittent fasting, not eating late at night).

The primary conclusion of the detailed analysis is that, for most of these diets, there is some evidence that they can deliver weight loss over some period of time. For example, the paper cites meta-analyses showing that a low-carb diet can produce weight loss at six months, though there is less evidence of sustained loss for a year. Other diets typically have less rich evidence. The Paleo diet, for example, has shown some favorable impacts on cholesterol, but these studies are still small. In terms of food timing, there is, again, some evidence for weight loss as a result of an intermittent fasting diet pattern and a general sense that eating late at night is not good.

The text comes down most favorably — in terms of individual diets — on the Mediterranean diet, where at least one large randomized trial showed weight loss and other health improvements (notably, less risk of stroke) in a higher-risk population. The author notes that this diet has the advantage of being “food-based” (as opposed to nutrient-based) and to represent a sustainable diet.

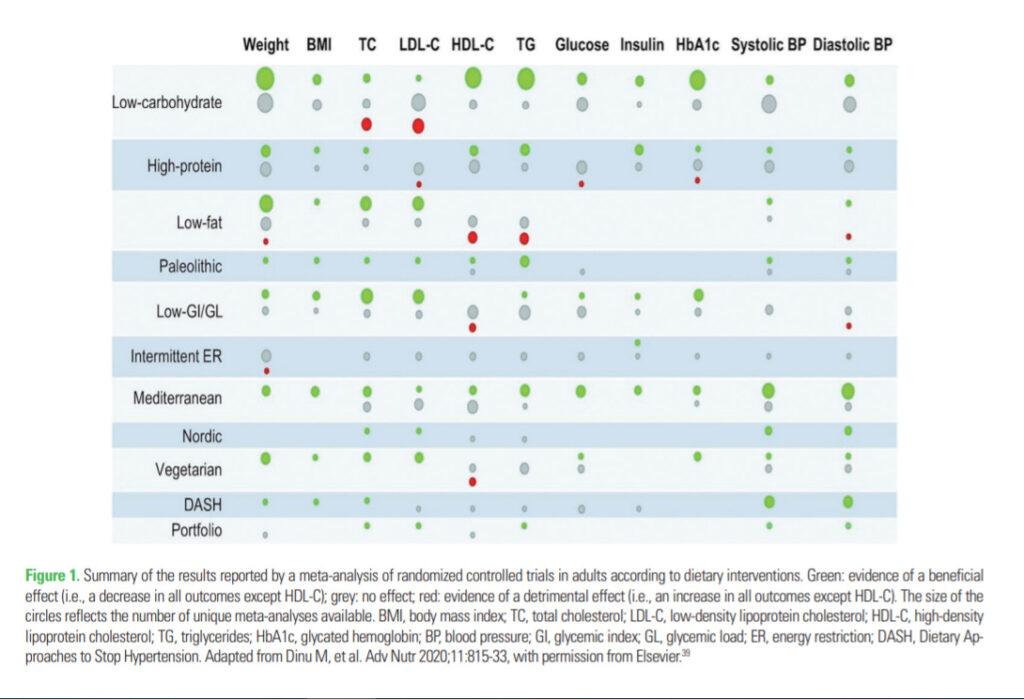

In summarizing, the paper contains a really excellent graph that effectively compares a whole slew of diets based on randomized evidence for their role in weight loss and other health metrics. (To nerd out for a moment, what is great about this graph is that it conveys a lot of information: many diets, many outcomes, the direction of the effects, and the number of studies. Also, great figure notes.)

The size of the circles indicates numbers of studies; of these diets, the volume of evidence on low-carbohydrate diets is the largest (low-carb diets would include Atkins, keto, and effectively any diet that limits carbs). For most outcomes — although notably not cholesterol — this dietary pattern looks either neutral or beneficial. Low-fat diets, in contrast, elicit more caution in terms of the possibility of increased triglycerides. The Mediterranean diet has the most consistent pattern of positive findings (as in, we do not see a lot of gray or red circles).

Obviously not all individual diets are covered in this graph, although it’s worth noting that many of the named diets you’re probably familiar with fall into one of these categories (especially low-fat and low-carb). It’s also true that if you go looking, you can find evidence for the value of most of these diets in either weight loss or other health metrics.

What does this mean?

The paper concludes with two thoughts:

- Reducing daily calorie intake is the most important factor for weight loss.

- The best diet for weight management is one that can be maintained in the long term.

There is no best diet. Or, no single best diet. The best diet for any purpose is one you can stick to. This extends beyond weight loss. Changing your diet for better diabetes management, or better cholesterol management, or blood pressure — all of these require being able to stick to it. If you are going to change how you eat, it’s crucial to do so in a way that is sustainable.

This is difficult. Long-term behavior change is a huge challenge for most of us. Altering diet, in particular, is hard for at least two reasons. First, there is a cognitive challenge in having to think about what you eat more than you might at baseline. Second, you’re hungry and that’s unpleasant. What is more, losing a significant amount of weight and keeping it off requires doing some of this more or less indefinitely.

The paper makes an interesting point early on about meal-replacement shakes. In a discussion of how to keep calories lower overall, the author suggests that meal replacements can be an effective way to do this, since they are easy. Saying, essentially, you’ll have this shake every day forever instead of breakfast is at least simple to follow. I think this point recognizes the inherent challenge in maintaining weight loss. It’s easy to start to slip.

In the end, the “best” diet is one that will let you happily maintain an overall lower calorie intake. And much of this is a personal question about what will work for you. I was talking with my family about this post over the holidays (thanks, rapid COVID tests!), and both Jesse and my mother raised the question of whether this literally means that a diet that contained only cake would be good for weight loss as long as it was not a lot of cake calories. In some ways, yes, although it would likely be problematic on other measures, like insulin. Also, and perhaps more importantly, as fun as it might sound, a diet of 1,800 calories a day of cake would leave you hungry and cranky and make you hate cake. So it really isn’t sustainable.

There is a broader point, though, which is that a sustainable diet could include cake. Just maybe less cake than currently, or less of something else. The catalyst moment people feel on January 1 can, as Katy Milkman points out in her amazing book How to Change, be an opportunity to jump-start something new. But that only works if it is something you can do. And something you want to do for you. So think about your motivations first and then think about what is sustainable.

Community Guidelines