My father (who is, I want to be clear, an extraordinary person who I love very much) is a notorious responder to health food advice. He is a person who, for example, consumes copious amounts of green tea and chia seeds, supposed keys to longevity and health. He is also a New York Times subscriber, so I thought of him as usual when, last week, Jane Brody published a column on the health benefits of coffee.

Coffee is frequently associated with positive health effects, as in this article, and sometimes with negative ones, as in this coverage from 2013 about how coffee leads to early death.

For me, these coffee-health links are kind of the classic example of observational-data-is-problematic. One of the health benefits cited in last week’s article is a lower risk of suicide. Beyond the obvious issue that this completely downplays the mental health issues which lead to suicide, it is completely implausible that such a link is causal.

However: a lot of people will read this article, and they will not all dismiss it. Maybe some of them will start drinking more coffee. Maybe they’ll be people like my dad — people who are not just reacting to this particular latest study, but doing all kinds of other things which also keep them healthy. And if that happens — if the people who change their behavior in response to this are healthier in other ways — it will reinforce the link between coffee and health in the observational data. If we came back next year to look at this relationship, it might be even larger than it was before. In other words, it may be that there isn’t just variation in who drinks the coffee in the first place, there may be variation in who changes their behavior when they see positive health news.

This idea — this self-reinforcing bias — this is the subject of one of my most recent published papers. Thinking about my dad, and about bias in the kinds of data I write about in my books, I got excited about whether I could find evidence of these patterns in the data.

But I didn’t look in coffee. Instead, I looked in vitamins.

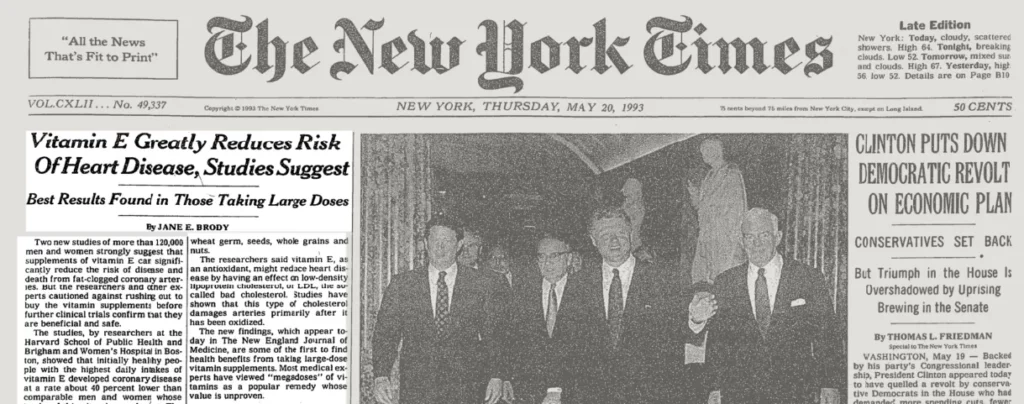

In 1993, several major studies suggested that people who consumed more vitamin E had lower risk of heart disease. These results were widely covered in many media outlets including the New York Times, where the article, also by Jane Brody, was published on page A1, above the fold. See below. This placement was a bigger deal in 1993.

The result was a heyday for Vitamin E. In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (or NHANES, for short), a nationally representative survey, the share of people reporting consuming vitamin E went from 4.5% to 12% over the periods between the early 1990s and 2000.

But the party ended abruptly in 2004, when a meta-analysis combining several small randomized trials suggested that Vitamin E not only did not help you live longer, it could kill you early if you took too much! This was also widely covered, if not as widely. The NYT headline was Large Doses of Vitamin E May Be Harmful. (I should be clear I’m not picking on the Times coverage here — it’s just nice to have the parallel over time, and they are the “paper of record” after all.)

Vitamin E consumption fell after 2004, back down to it’s early 1990s levels by 2010.

What I was interested in, though, wasn’t the fact that anyone reacted to this news. It was the question of who reacted. To figure that out, I took this NHANES data and I calculated, at different points in time, the correlation between taking vitamin E and characteristics like education and exercise. The inspired-by-dad theory I outlined above suggests that in time periods when vitamin E is more recommended (i.e. between 1993 and 2004) the uptake might be larger among more educated people or those who also exercise. This greater uptake will mean there is a larger positive correlation between vitamin E consumption and those variables in this intermediate “vitamin-E-is-good” period than either before or after.

These correlations — in the “before”, “during” and “after” periods are shown in the graph below. They line up the way the theory predicts. During the intermediate period, vitamin E is more positively correlated with education, income, exercising and eating a good diet (which I define as having vegetables). It’s more negatively correlated with a “bad” health behavior, smoking.

You may say, okay, so what? I might be right about these differences in take-up, but does it matter for what we’d conclude about the health effects? It turns out: yes. During this intermediate period, Vitamin E is also more predictive of good heart health and, yes, of survival. Even if we adjust for what we observe about individuals in the data, we would still be more bullish on vitamin E’s health effects in this intermediate period.

It’s not just vitamin E, either. I’ve got a few more examples in the paper, the one I like best being about sugar. Sugar used to be the best! As a child of the 80s, I recall the “complete breakfast”: toast with jam, frosted sugar-shack-sugar-bombs-with-marshmallows, large juice. Then the fun police arrived, and now sugar is totally out.

(This isn’t my feelings; official dietary guidelines have also changed their sugar attitude over time).

I’m not here to comment about what is right, but just to note that over this period — say, from 1988 through the present — as we got more and more negative on sugar, the consumers of sugar changed. You can see this in the graph below — same as the one above, but with sugar this time. In the earliest period of the data education is actually positively correlated with this measure of sugar consumption, but it becomes negative over time.

As result, in the data, sugar starts to look…a lot worse for you over time. In the earliest period of the data there is no observed correlation between the sugar measure and BMI (see below) but by the latest period, it’s hugely correlated. The “sugar-makes-you-fat” story only shows up in the last few years, coincidentally during the period when sugar is less consumed by individuals who exercise, do not smoke and are better educated.

So…sugar doesn’t make you fat? Vitamin E kills you? Or doesn’t? Maybe! My point here isn’t that one of these results is “right” or “wrong”. It is simply that this kind of data may be even more problematic than we expected in the face of this kind of uneven individual reaction to it.

To get back to the title. Coffee is very unlikely to be the fountain of youth, any more than chia seeds are. It doesn’t make me love it any less, though.

Community Guidelines