Quick note: I’m from the U.K. and so I use the term “postnatal” rather than “postpartum,” which would be the equivalent phrasing in the U.S.

Around 8 p.m. each day, once the kids were tucked up in bed, I’d take the dog for a walk — just the two of us. The smell of the balmy Mediterranean evening, a warm glow slowly setting on the horizon. I’d walk to a park — far enough from home to prevent bumping into someone I knew, but close enough not to arouse suspicion — to sit on a bench. And cry.

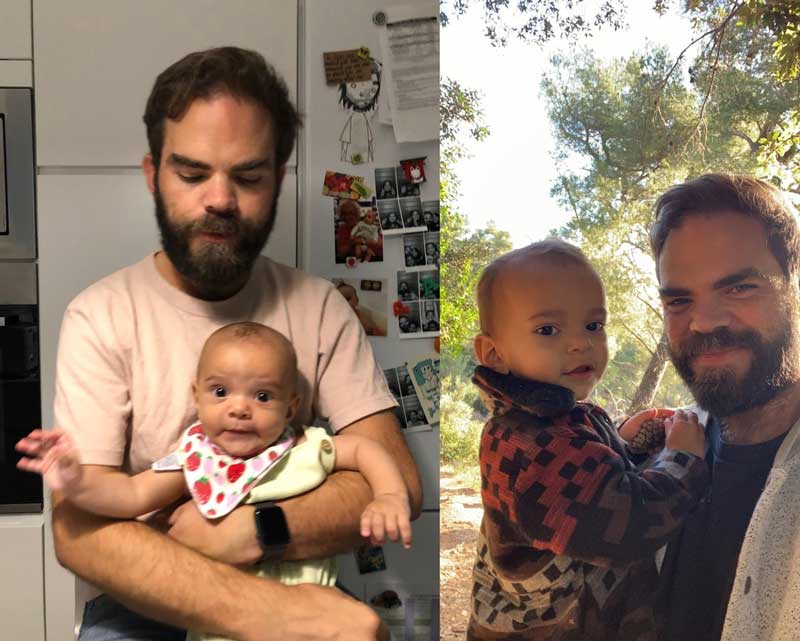

I spent most of the summer of 2019 wondering what was wrong with me, and why I didn’t love my son. He was born three months earlier: happy, healthy, and everything we could have asked for. After settling into the unique cadence new parents face — moving abruptly between adorable vignettes and constant sleep deprivation — I started to sense something wasn’t right. The thought didn’t arrive fully formed; a dull background static, initially attributed to exhaustion. But when it remained, after even the occasional eight hours of sleep, I started to question what I was feeling. A darkness had crept upon me since his birth. I was getting angry all the time, over the smallest things. I didn’t want to be close to my wife. Didn’t want to play with my daughter. Didn’t want to talk to friends. Getting through each day was a struggle, like wading through mud with a 50-kilo weight strapped to my back. And, most painfully of all, I didn’t want to be near my son.

Hearing him cry was like nails scraping down a chalkboard. And he cried — a lot. At least I thought he did, though I now realise my mind was playing tricks on me, blowing this small thing out of proportion, like it was treating everything else: molehills transformed into mountains, trapping me within. I avoided any attempt to solve the problem he had, because my mind told me he’d only start crying again soon after. What would even be the point?

So I shrunk away. From being a husband. From being a father. I went to a dark place.

While sitting on that bench crying, my eternally sad basset hound watching tears run down my face, I tried to get a handle on what was happening. With hindsight, I’m lucky this was my second child and I had some kind of benchmark to compare it against. I knew that what I was feeling wasn’t “normal,” so I started searching online about why I might be feeling this way. Whilst googling things like new dad sad and why am I crying new dad, I came across an article written by a doctor who had trouble connecting with his second child. I read the symptoms and felt an odd sense of relief: ongoing feelings of anger towards your partner and child, feeling numb and empty, increased irritability, increased use of alcohol, significant weight gain or loss, loss of interest in work or hobbies, feeling sad and crying for no reason.

Paternal postnatal depression. I had no idea it existed.

I was aware of postnatal depression. All dads-to-be are. We’re warned about it, advised on the signs to look out for when your wife, or other women in your life, have a baby. But there were slim pickings when trying to learn more about a father’s mental health after a newborn comes into their life. On the World Health Organization’s website, searching for paternal mental health returned the non-helpful “Did you mean: maternal mental health?” Paternal postnatal depression still returns zero results on the UK National Health Service’s website, and back in 2019 I’d read that some mental health charities wouldn’t allow male writers to use the term paternal postnatal depression when talking about the problem — they were only allowed to refer to it as “depression for dads.”

PPND is not as widely acknowledged or well-researched as postnatal depression in mothers, so the papers we rely on are spread across decades, not years. A 2003 paper said it could affect as many as 25% of new fathers (or 50% for those whose partners already show signs of postnatal depression), a 2015 paper from Japan pegged the number at a very precise 13.6%, whilst a meta-analysis from 2010 suggested the figure as somewhere between 8% and 13%. But it’s impossible to know the true number, because men are less likely to seek help, to reveal negative thoughts to partners, friends, or health-care professionals, or to be routinely screened in the way new mothers are.

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) has become the go-to method of screening postnatal depression in new mothers, and many countries will routinely administer it, passing cases forward if the score indicates the potential of PND. But fathers are not asked the same questions, even though research suggests that the same questionnaire, with a lower cut-off point, would uncover many cases.

How many cases might that be? Let’s take a look at the UK, where I’m from and where the EPDS originated. Assuming the 2019 ONS figures of 640,370 new babies born in the UK (and removing 12.8% of lone-parent mother households), there are around 558,000 new fathers in the UK each year. Even assuming a fairly conservative estimate of 10% of new fathers experiencing PPND, that means as many as 55,000 men, each and every year, with the vast majority suffering in silence. Research shows the knock-on effects of undiagnosed cases can harm generations to come — for example, with children of depressed fathers twice as likely to develop a psychiatric disorder by age 7, and 2.8 times as likely to use mental health services when they become adults.

The changes happening in fatherhood are altering the very landscape of parenting. A problem previously thought of as only happening to mums now needs to be considered for dads too. As men take more active roles in the upbringing of their children — with many attempting to equally co-parent, or the increasing number choosing to become stay-at-home dads — we’re shouldering the burden of sleep deprivation, the pressure to be both a perfect parent and productive employee, and the many things that have contributed to postnatal depression in women over the years.

When I look back on photos from that time, I don’t recognise the man in the picture. Of course, there are photos of me holding my son and smiling; I knew well enough to put on a happy face for those. But there are other photos — ones where I don’t know I’m in the background, walking in the park, or sitting on the sofa. And that man looks broken. Truly defeated. Empty. Shattered, in every meaning of the word. I look at him and realise what my wife must have felt, seeing the man she loves so far removed from the person she fell in love with. I needed help. I’m thankful that she was there to give it.

We figured it out together. Worked on a routine to get things back on track. I started therapy, a daily meditation practice, and exercised regularly. Worked hard to get a good routine back into my daily life. Cut out bad habits that were putting me in a negative headspace. And purposefully spent time with my son, on our own, building the belief that I could do this.

One thing that helped was opening up to other dads in my life. I started talking to friends about my problems, and realised that I wasn’t alone in these feelings. When I started to feel better, I began reaching out to friends who had recently become dads, making sure they were doing okay (and telling them it was fine to talk if they weren’t). I started writing about my experience in the hope it might help others — these essays became the start of The New Fatherhood, a weekly newsletter I’ve continued writing about the highs and lows of being a modern dad. Since first sharing my PPND story, I’ve had dozens of emails from people thanking me for opening up, helping them identify the same symptoms, encouraged to seek help. I’ve continued writing about the importance of mental health since. In October last year, I took the revenue from my newsletter and used it to create a direct-action therapy fund, helping dads get access to therapeutic help, no matter where they are. The dads (and curious mums) reading contributed enough to help almost a dozen dads.

Paternal postnatal depression tears families apart. It makes men resent their children — at one of the most pivotal, wonderful times of their lives, and maybe forever — because they don’t get the help they need. There are thousands of undiagnosed dads, silently suffering, unsure of why they feel this way. Taking it out on themselves. Their partners. Their family and friends. And, worst of all, on their children. It’s only through bringing these issues into the open — be it a newsletter about fatherhood, or a moment of vulnerability between two friends — that we can hope to change things for the better.

Community Guidelines

Log in

Thank you so much for sharing! Such an important topic.

Thank you for sharing and spreading awareness. Four years ago when my husband and I were at a newborn appointment, the Ped gave me the EPDS and we laughed about how he would have failed it if he had to fill it out. Still, it didn’t exactly click for us that something was wrong. We assumed dads couldn’t get PPD but all the signs were there. Eventually he got the help he needed and we’re all much better now. I wish we had read a story like yours 4 years ago to help understand what was going on and not laugh it off.

Thank you so much for sharing! It is a very common misconception, from all of the parenting reading I have done, that parents who don’t give birth cannot experience postpartum depression. I’m an adoptive Mom and the research and resources should include all parents. Fathers, parents via adoption and surrogacy and birth parents, too! Your advocacy and transparency will go a long way to ensuring that all parents are included when looking at changing access to diagnosis and treat ment!