I’m going to be honest with you: breastfeeding my first baby was hard. Really hard. There was the elaborate tube-taping system in the hospital to avoid “nipple confusion.” There was pumping at all hours, trying to figure out when to do it without sabotaging the next feeding. And there was that moment at my brother’s wedding, sitting in a sweltering closet trying to get a screaming 7-week-old to latch while the party went on outside.

With my second, it was completely different — easy, even. But that first experience taught me something important: the difficulty of breastfeeding is made exponentially worse by the pressure we put on ourselves, fueled by claims that breast milk is “liquid gold” that will make our babies smarter, healthier, and basically superhuman.

The clear messaging: Breastfeeding gives your baby the “best” start; it’s the key to future success on all kinds of dimensions. You’ll hear, often, that these claims are based on data. Is this true? It turns out, not completely. Let’s look at what the data actually says about the benefits of breastfeeding.

Note: if you want to read a longer version, with even more detail on the studies, you can find the full chapter from Cribsheet here.

A closer look at the messaging

If you’ve spent any time on parenting websites, you’ve seen the lists. Breastfeeding supposedly prevents everything from ear infections to obesity to juvenile arthritis. It boosts IQ. It helps moms lose weight, resist stress, and — I kid you not — form better friendships.

The problem is that most of these claims are based on flawed research. Here’s why: In developed countries, women who breastfeed are typically wealthier and more educated than those who don’t. This wasn’t always true; breastfeeding rates actually dropped dramatically through the mid-20th century as formula became more “modern.” But public health campaigns since the 1970s have pushed breastfeeding, and the uptake has been highest among higher-income, better-educated women.

These differences in who breastfeeds and who does not create a problem for researchers. Many of the outcomes associated with breastfeeding are strongly associated with these other differences. If we see better test scores among children who are breastfed, it is difficult to know whether that is due to the fact that their families are more educated and richer, or due to the breastfeeding.

There are research papers that do a better job separating correlation and causation, but we need to look carefully for them. To give a sense of this approach, we can look at two of the most common claims about breastfeeding: that it raises IQ, and that it prevents SIDS.

Breastfeeding and IQ

The “breastfeeding makes babies smarter” claim is one of the most persistent. It is easy to find studies linking IQ scores to time spent breastfeeding. One example paper using Swedish data showed that children who were breastfed longer performed better on cognitive tests at 13 months and 5 years.

The problem — in this paper and others — is that the mothers who nursed for longer were also different in other dimensions. When researchers adjust for these differences, the gaps between breastfed and non-breastfed children get smaller. We still see these differences, but we have to wonder: what if you could adjust for them more completely?

The best evidence comes from papers that do a better job adjusting for these differences. One successful approach is to use a sibling design, where researchers use data from families in which one child was breastfed and one was not. They compare within families, which allows them to hold constant everything about the mother. The best of these studies — here is one example — shows no impact on IQ when comparing within siblings.

Another approach with a stronger claim to causality is a randomized trial. We have one example of this in breastfeeding: the massive PROBIT study in Belarus, which randomly assigned some mothers to breastfeeding promotion. In their objective measures of cognitive performance, they found no impact of breastfeeding on IQ.

Overall, the correlations observed in the data are unlikely to be causal for this outcome.

Breastfeeding and SIDS

You’ll often see SIDS (Sudden Infant Death Syndrome) on lists of things breastfeeding prevents. The emotional weight of this claim is enormous. What parent wouldn’t do everything to prevent such a tragedy?

The data, however, does not support this link.

SIDS is rare (about 1 in 1,800 births) and even rarer, perhaps 1 in 10,000, among babies with no other risk factors like prematurity or stomach sleeping. This rarity makes it incredibly hard to study.

As a result, most research on SIDS and breastfeeding uses case-control studies: they interview parents whose babies died of SIDS and compare them to parents of living babies. Some of these studies do show that breastfed babies are less likely to die of SIDS. But the studies have two problems. The first is the same issue as the IQ data: when researchers adjust for other factors, the effect shrinks or disappears.

In this case, there is a second concern: how the subjects are recruited. In many cases, the approach to finding the parents whose babies died of SIDS is totally different from the approach of finding the control group. This introduces even more issues where the two groups are not the same. Studies that do a better job addressing this — like one that compared babies visited by the same home health nurse — show no SIDS risk from formula feeding.

Are there any benefits to breastfeeding?

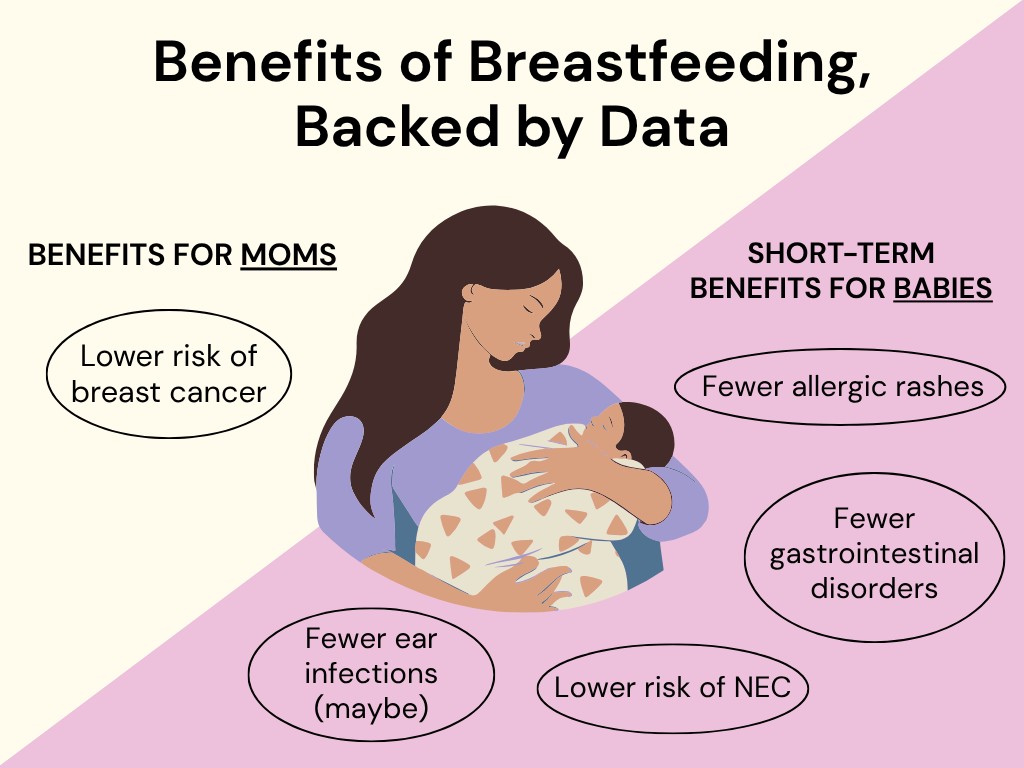

Yes. Breastfeeding does seem to reduce some infections in the baby’s first year of life. Reliable data, much of it from the randomized PROBIT trial, shows a reduction in gastrointestinal issues in the first year, a reduction in the risk of eczema in this first year, and possibly reduced ear infections. There is also better evidence for benefits in NICU babies, who are at risk for necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC).

These aren’t huge effects — your exclusively breastfed baby can (and likely will) still get plenty of colds — but they’re real. The mechanism makes sense too: breast milk contains antibodies that help fight infection, especially early on.

The other benefits to breastfeeding that have some better support in the data are the reduction in the risk of breast cancer for the mom. Multiple studies show that breastfeeding may reduce breast cancer risk by 20-30%. Since breast cancer affects about 1 in 8 women, this is meaningful. The mechanism is plausible too — breastfeeding changes breast cells and lowers estrogen production, both of which reduce cancer risk.

Overall, it is right to say that breastfeeding has some benefits, but they are far smaller than often claimed.

Closing thoughts

After sifting through the research, and, again, you can read more about the data here, this is what we’re left with: some modest short-term health benefits for babies (fewer GI infections, maybe fewer ear infections) and one potentially significant long-term benefit for moms (lower breast cancer risk). The list is much shorter than the one plastered all over parenting websites.

This isn’t to say you shouldn’t breastfeed. If you want to and it works for you, that’s wonderful. I’m glad I nursed both of my kids, mainly because I enjoyed those quiet moments together. That personal satisfaction? It’s a completely valid reason to breastfeed.

But if breastfeeding doesn’t work out, or if you choose not to do it, your baby is going to be fine. The data simply doesn’t support the claim that formula feeding is a lesser alternative or that you’re denying your child some crucial advantage.

Dr. Spock had it right back in the 1980s: try it if you want to, but the most convincing evidence for breastfeeding comes from mothers who enjoyed the experience of closeness with their babies. That’s not about IQ points or disease prevention. It’s about whether it works for your family.

The bottom line

- The IQ claims don’t hold up. When looking at high-quality studies — such as those that compare siblings and large randomized trials — these supposed cognitive benefits disappear.

- Short-term infection protection is real, but modest. Breastfeeding seems to reduce gastrointestinal infections, eczema, and possibly ear infections in the first year.

- The most robust evidence is for breast cancer risk reduction — potentially 20-30% lower risk for women who breastfeed.

- If breastfeeding works for you, wonderful. If it doesn’t work out or you choose not to do it, your baby will be fine.

Log in